|

"...not a single

one of the Montalbano stories was written without a specific prompting, I am

tempted to say. Writing just for the sake of writing is not my sort of thing. I

would even say I'm incapable of it."

(Camilleri, preface,

'Montalbano's First Case & Other Stories, 2008/16)

Perhaps, like the

protagonist in Borges' celebrated story

The

Circular Ruins (1940), Camilleri thinks he's just one in an infinite chain

of dreamers who, in this case, instead of dreaming new dreamers into existence,

dreams novels endlessly.

With writers like

this, it gets difficult to tell when their imaginations have run dry or when

they've actually advanced the narrative. Is Camilleri like this? Maybe by the

fifteenth or sixteenth Montalbano mystery you're thinking this cop should die,

go out in a blaze of mafiosi bullets or succumb to food poisoning at his

favorite trattoria, Enzo's, or maybe get knifed by his long suffering lover

Livia or one of the many femme fatales he investigates a little too

personally in person.

'the earth smelled

as good as the sea'

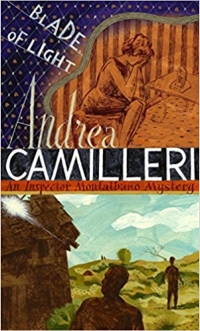

Blade of Light (2012)

is a bit like this, seeds the veteran Montalbano reader with doubt. The deja

vu seems stultifying at times, and you wonder if you can make it to the

end, even though the writing is the usual easy read, as loose as silver in the

pocket. Once again -- for anyone who has read the earlier novels in the series

-- it starts with Montalbano dreaming, this time of a coffin in an open field.

Ah yes, his mystic

Sicilian surrealism gambit, where events are foreseen by the great detective as

if he's tapped into the ancient oracles of the nearby Valley of the Temples.

Well, it's an attractive method, sure enough, unless you're thinking Camilleri

has used this old trick one too many times, and do I care who is in the coffin?

In his dream, it's the Commissioner Bonetti-Alderighi, his immediate superior

and tormentor... it's funny, although you suspect that if a coffin should be

found, it won't be the Commissioner's.

A farmer called

Intelisano comes in to the station to report that someone unknown has installed

a padlocked door on an abandoned cottage on one of his properties. So the dream

farce is set aside for the moment as Montalbano investigates the mystery of the

padlocked door and a couple of Tunisian farm labourers who really don't look

like manual workers at all, who just might be into smuggling some heavy weapons

back to the rebels in the old country. Montalbano assumes a light disguise --

hat, shades, a convivial manner -- approaches the ruined house, sees a flash of

light from the loft (the poetic "blade of light" that provides the title),

suspects he's under surveillance by someone using binoculars.

But this is really a

job for the anti-terrorism unit. The other crime is more his speed -- the rape

and robbery of a young married woman late at night when delivering the day's

cash from her husband's supermart to a deposit box on a deserted midnight

street. So, when is Montalbano dreaming, when is he not? All these women and

their tricks. Montalbano has a few tricks of his own, of course, and while he's

well-known from the crime-beat interviews on local television, and is therefore

a local celebrity, women should be wary. While not exactly a one-night stand

artist, Montalbano has a polite way of shucking his women like fish bones or

crimes solved and filed.

And who is the woman

here? Marian, an art gallery maven who pounces on Montalbano like cat finding a

warm stone to lie beside. Of course his main throb Livia is giving him a hard

time. And as usual she's way up there in Genoa suffering from some sort of

depression that's more like a guilt trip ploy, something to make Montalbano

move or get off the pot... yet turns out to be a premonition of nasty things to

come. So there are forces at work here that subjugate any crimes of fidelity,

robbery, murder, and conspiracy, and all of these things are going on in Blade

of Light.

Just what is a "blade

of light"? you ask. A forced poeticism? Another edition goes by the title 'A

Beam of Light', a more ordinary figure (perhaps you'd call it a dead metaphor).

'Blade" is better. When you reach the ending, and reflect on what has happened,

the irony of this figure is bitter sweet -- bitter for Montalbano, sweet for

the reader (who is, of course, a connoisseur of Camilleri's Sicilian epic).

Guilt, revulsion, irresponsibility. It's quite the pivot, a piece of dark

psychology that perhaps doesn't leave Montalbano in the best light. You do need

to know something of Montalbano's history from the earlier novels -- especially

The Snack Thief (number 3) -- to understand absolutely what has gone down,

although the author does insert some history to help finesse the moment.

Nest of Vipers...

Montalbano's First Case... Pyramid of Mud... 20, 21, 22...

© LR June

2017

*Check out LR's

OUTLAW

ACADEMIC »»

or LR's novel

RADIO

BRAZIL »»

|