|

While this danse

macabre is the key to the through-line in Camilleri's narrative, the plot

is immediately driven by the disappearance of Fazio, Montalbano's main capo, a

steady-as-she-goes cop that you've become familiar with from the previous

novels, which personalizes the crisis for both the Inspector and the reader. To

be sure it's a police fiction cliché, yet here it's just a fact, and the

tension builds as you realize that Fazio has been abducted, perhaps killed, as

his mission at the port of Vigàta was unofficial, and his colleagues

don't know what he was up to. Seems he was helping out an old school friend, a

former ballet dancer, who has suspicions about goings on with the fishing fleet

and a certain warehouse that he has been observing through a telescope from his

apartment. Turns out this man, this dancer -- Manzzella -- is a habitual

voyeur, enjoys spying on his neighbours, and since he left his wife, is now

taking a walk on the wild side.

Here the story might

remind you of The Crying Game, Neil Jordan's 1992 film about transsexual love

and terrorism, but only distantly, as a shared exoticism rather than a formula

theft. There are several very good scenes along the way, especially when

Montalbano follows a tip that Fazio was seen struggling with two men in 'the

territory of the dry wells" at Monte Scibetta, a known Mafia body dump. This

sequence produces a couple of bodies, then ends up in an abandoned highway

tunnel. Darkness, amnesia, and bullets -- can anything good come from any of

this?

'Without anyone

noticing, Montalbano superstitiously touched his balls to ward off bad

luck'

'The night was soft

and clear and windless. And the moon, instead of resting over the orchards, was

floating on the sea'

At one juncture,

Montalbano visits a murder house, moves like a somnambulist through the moonlit

rooms reconstructing the crime. It's a nightmare, a seance for detectives and

madmen with the art of remote viewing. The house stinks of death, is a theatre

of torture and sadism. This self-hypnosis induces seeing through blindness, a

trap for coincidence and fate. It's occultism and Montalbano knows it, despises

himself for indulging the ritual, this taboo possession with its grotesque

voyeurism and shabby exorcism. But he sees it all, the two torturers shooting

their victim in the foot, then forcing him to dance, to flutter until he dies.

Then they take a shower. Why?

'To cleanse

themselves for human society as humans, not as the beasts they

were'

There's no question

that this is one of Camilleri's best Montalbano novels because, even though

many of the characters and the situations remain the same, the story runs

against the grain, is anti-romantic. Montalbano is 57 here, 'in the twilight of

his career', and the issues and crimes he deals with really have no happy

resolution. He has a romance with a blonde, sure, but it's a vulgar exercise in

political sex, not love. He uncovers a heinous crime of international

significance, but it isn't something the government can admit, let alone

punish. He does stage some local justice, but you know it's tabloid, not

institutional.

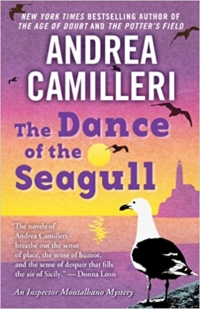

You might wonder -- as

Camilleri has a lot of experience teaching theatre direction -- if this novel

owes anything to Chekov's play The Seagull (1896). In this symbolist drama,

which was avant garde for the times, the seagull is a gift to a young actress

from a crass suitor who shot the bird because he had nothing better to do. But

the actress prefers a visiting writer who thinks the incident would make an

excellent short story. This sort of internal aesthetic commentary anticipates

the post-modern fashion of blurring the alienation wall between the author and

his characters... a technique Camilleri engages occasionally in the Montalbano

series. And towards the end of The Dance of the Seagull, Montalbano indeed

wonders how "Camilleri" is going to get him out of the situation he finds

himself in. So, you could say there's an oblique influence, intellectual rather

than story-wise, where Camilleri has borrowed a symbolic motif, adapting it for

his own design.

As I've said before

elsewhere, Andrea Camilleri is a major writer, regardless of genre. He walks

with beauty.

© LR April

2017

*Check out LR's

OUTLAW

ACADEMIC »»

or LR's novel

RADIO

BRAZIL »»

|