|

"She must have been

very beautiful. A fantastic body," said the public prosecutor, his eyes

glistening with excitement.

Tommaseo, the

prosecutor, has intercepted Inspector Montalbano on the path. Notice how

Camilleri achieves two things at once with very few words: a sense of the

victim, a sense of the prosecutor. Other than a couple of other details -- she

has a tattoo of a four wing Sphinx moth and a considerable part of her face has

been blown off by a heavy bullet -- you really don't need to know anything else

about the crime scene.

Just concentrate on

Montalbano, who becomes your alter-ego:

'It used to be that

he felt afraid of dying people, while the dead made no impression on him.

Whereas now, and for the past few years he could no longer bear the sight of

people cut down in their youth.'

Montalbano is 56 here,

really on the skids. He's broken up with his girlfriend Livia and his police

station hasn't received its allotment of gasoline, so the cops are forced to

use their own cars, buy fuel on their own dime. It's a shitty situation, a

Berlusconi moment, an Italian cause de grace as the country crawls

through the mire of its own corruption, economic malfeasance, open borders,

senseless love, senseless death... auribus teneo lupum... untenable,

citizen.

And who's the

beautiful corpse? A Russian girl, another economic migrant, a 'dancer', a maid,

who certainly could be something else, for, who else ends up like a depraved

art exhibit in an illegal garbage dump if not involved in the sleazy world of

greedy sex and greedy money? So you're thinking. The only clue is the purpurin

resin beneath her fingernails, whatever purpurin is.

There's another case,

more amusing than anything, a fellow by the name of Picarella has gone missing,

kidnapped his wife asserts, even though no ransom demand has been received.

Then a guy with a gold chain and a Ferrari shows up at the Vigàta

station, tells Montalbano he saw Picarella dancing with a chick in a Havana

nightclub that weekend, shows him a photo. What does Montalbano hate the most?

Di Noto, the guy with the gold chain, or his Ferrari or the fact that now he

has to confront Picarella's wife, Ciccina, the rich vixen with connections in

the upper echelons, can make his life a misery with his boss the Commissioner

with the double-barrelled name, Bonetti-Alderighi? While Montalbano isn't

resentful towards the upper classes per se, he definitely doesn't like

playboys with gold chains and ostentatious cars, even if they're Italian cars.

Bear in mind that one of his good friends, Zito, the TV journalist, is a

communist. And when things aren't going well, it's easy to get pissed off like

a communist, export the pain.

Broadcast of the

sphinx tattoo draws witnesses. An old keyhole voyeur called Graceffa comes in

the station, tells Montalbano about the Russian maid he had for a month. Katya.

He wanted sex ("I'm still a man") but nothing doing. Then Montalbano's old

Swedish flame Ingrid shows up and reveals that she too had a Russian maid for a

month or two and she disappeared, taking 400,000 Euros in jewelry. Irina Ilych.

And she has the sphinx tattoo and was referred through a Catholic charity

called Benevolence, run by some priests and their friends, specialize in

providing foreign "home-care assistants". An arrogant cleric called Monsignor

Pisicchio runs the show; after a testy interview, Montalbano. 'smells a

rat'.

Montalbano goes home,

eats, sits down in front of the TV.

'...the television

had been presenting the same news story for years; the only things that changed

were the names....

'In Fela the

charred remains of a farmer previously convicted of collaborating with the

mafia were found in his car (the previous evening it had been the turn of an

accountant in Cuculiana, likewise a collaborator, to be charred).

'In the countryside

around Vibera the search for a mafioso on the run for seven years intensified

(the previous day the search for another mafioso, on the run for only five

years, had intensified in the countryside around Pozzolillo).

'In Roccabumera,

carabineri and criminals exchanged gunfire....'

I've shortened the

montage here, but you get the point. It's like the old newsreel roundup used to

condense the News for movie houses in the days before television, and used very

effectively at the beginning of Citizen Kane and Shangri La (the unreleased,

first version) (both assembled by Robert Wise, I believe). For Camilleri, the

montage is incantatory, almost a lament, but funny. The absurdity of it all is

like asking how many detectives does it take to fix a light bulb.

Montalbano retires to

bed with a novel -- 'proclaimed a masterpiece in the local paper' -- but ends

up throwing it against the wall. Once again it's the portrait of Montalbano the

man caught in the crossfire of modern life and death that carries the action,

because the imagery of serial crime and its culture in Montelusa province

remains much the same book to book in the series. The perpetual redundancy of a

job where law and (dis)order make a mockery of creative achievement is

demoralizing. The natives are incorrigibles. Sicilians, Italians, Euros... the

World.

So, half-way through

the story and still no gasoline... and a bunch of mouthy priests who use the

Old Boys network to put heat on Montalbano to cease and desist. Sergeant

Fazio's car is in worse shape than Columbo's. Fazio and Montalbano get stopped

in a carabinieri roadblock, fines being written and more humiliation until the

marshal recognizes Montalbano, waves them through. If it wasn't for the Carlo

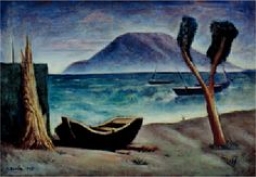

Carrà paintings at a Notary's apartment they visit to see what they can

learn about his Russian maid, the day would've been another exasperating

experience.

'The landscape by

Tosi was superb, but when standing before Carrà's seascape, Montalbano

was moved almost to tears.'

This is interesting,

because, if you know that Carrà, like many of his Futurist colleagues,

was a supporter of Mussolini in the inter-war period, you might wonder how the

liberal egalitarian Inspector Montalbano could respond so positively to the

work of a fascist. Of course if you look at any of Carrà's seascapes,

you'd be hard pressed to see anything political in their faintly metaphysical

castings. Montalbano responds to beauty, which is feminine in his world view,

so when he pursues the killer of a woman, he's like an artist in search of a

subject.

Here, the priests are

in his way:

'How many

politicians with powerful connections in Rome, and all of them, whether of the

Right or the Left, with their wheels greased by priests, would take to the

field in defence of Monsignor Pisicchio and Benevolence?'

His boss phones from

Rome, tells him to step back, pass the case to the Flying Squad.

Montalbano

thinks:

'You eat, shit,

sleep, read a few novels, and every now and then you go to the movies. And

that's it. You don't like to travel, you don't go in for sports, you have no

hobbies, and when you come right down to it, you don't even have a few friends

with whom to spend a few hours....'

The self-pity doesn't

overcome the driving humour, that Camillerian sense of the absurd, where farce

and tragedy struggle for not only control of the News Channel but his own

self-worth. The decline in the status quo is both societal and personal. It's a

Zorba moment -- he can dance or go to sleep. He sleeps.

No, The Wings of the

Sphinx isn't the best novel in the series, yet it has some very good writing

and human insight along the way. It's almost scrubbed clean of romance, and the

shading of Montalbano's character shows him deteriorating almost to the edge of

despair. He's not really a detective, he's an artist, in the way that we're all

artists when frustration stands between us and beauty. And the death of romance

will do this every time. The dead girl in the dump isn't Livia, but it some

ways it is.

How does it end?

Better than you might think: tutte le strade condocono a Roma... all

roads lead to Rome.

© LR May

2017

*Check out LR's

OUTLAW

ACADEMIC »»

or LR's novel

RADIO

BRAZIL »»

|