Blow-Up

(originally The Devil's Drool): film vs. story

The movie version of

Blow-Up marks the beginning of Antonioni's decline as a filmmaker. The messy

narrative with its impotent. symbolisms and pop culture asides do no favors for

either himself or Cortazar, although sometimes they almost succeed. Only the

central metaphor of the photographer trying to unravel a mystery via a series

of blow ups of a man in gray remains, and for Antonioni this man is a body,

possibly the victim of a murder, not a mysterious man in a car who sits

watching a woman and a youth on the tip of an island in the Seine, as in

Cortazar's story. While he seems to have understood the mystical possibilities

inherent in the story, Antonioni was under the influence of the absurdist style

of 50's/60's theatre, in particular Samuel Beckett and his acolyte Harold

Pinter. While Tonino Guerro, a seasoned Italian screenwriter is listed as the

main writer along with Antonioni, the absurdist stage trickery and Platonic

logic is all too evident in the perceptual conundrum presented by the tennis

game with no ball. You could argue that it repeats the lesson of the "photo

blow-up" or dismiss it as redundant and distracting. While enigma is central to

the surrealist way of doing business, as a closing scene it does nothing to

advance our understanding of what went down in the park.

The original title of

the Cortazar story was The Devil's Drool (Las Babas del Diablo) and

draws us closer to the suspicion that 'the man in gray' (gray hat) is a

pedophile who is using the woman as a procuress to snare the youth for a

threesome or for his enjoyment alone. Yet you just don't know. He might be the

woman's husband, tolerating her desire to seduce a toyboy... or, for that

matter, the whole situation could be sexually innocent. The youth might be the

woman's son... or their son, perhaps estranged, and the event is an attempted

reconciliation. The amateur photographer's perception is merely a process of

understanding... or misunderstanding. The suspicion is that a crime is being

committed, and, like a detective, the photographer is driven by a need to

understand it, the why and the wherefore, and to do this, he needs to get

closer to the mise en scene. Thus he enlarges the photograph to the point of

abstraction and finds himself further away from the truth, but closer to

belief. There's an element of madness in Michel's narrative, as if he is

replaying an event from a former life, and his blow-up is a Rorschach blot

excavating his despair, his guilt, his impotency.

'The photo had been

taken, the time had run out, gone; we were so far from one another, the abusive

act had certainly taken place, the tears already shed, and the rest conjecture

and sorrow. All at once the order was inverted, they were alive, moving, they

were deciding and had decided, they were going to their future; and I on this

side, prisoner of another time, in a room on the fifth floor, to not know who

they were, that woman, that man, and that boy, to be only the lens of my

camera, something fixed, rigid, incapable of intervention.'

This is quite

different from Antonioni's version of the same scene, the same metaphor. For

Antonioni's photog there is no triangle of sinister intent going on in the

park, although something sinister emerges later. His photographer, Thomas, is a

professional (modelled on the well-known London fashion photographer David

Bailey) and he's wandering in the park with his camera, happens to photograph a

woman and her male lover frolicing. The woman confronts the photog, demands the

film, but to no avail. The discovery of the body in the border bushes is an

accident of the blow-ups, a surprise, not something he does to confirm a

suspicion -- as in Cortazar's story -- and in fact might be a hallucination

created by the developing process. First the blow-ups reveal a man with a gun

in the bushes, then another, the body, presumably the lover. The photographer

returns to the park at dusk but finds no body. So there is no solution to the

mystery, only a confirmation of unreality. It should be noted that this

arthouse film was very popular at the time (1967) as its mix of pop culture

characters and arcane imagery appealed to the psychedelic preferences of a

generation quite willing to believe that "nothing is real'.

Anyone reading

Cortázar's story after seeing Antonioni's film would be confused, and

see little resemblance, except perhaps in the metaphysical outreach. David

Hemmings, who played Thomas the photographer, says the first script he was

given was 16 pages entitled

'A Girl, a Photographer,

and a Beautiful April Morning which raises the possibility that

Cortázar's story was perhaps a later addition to the project. By the

time he made Blow-Up, Antonioni had become committed to the auteur idea of

improvising films on the fly. Godard was doing it, so why not him? Often the

literary property was just an excuse to find financial backing, although in

Antonioni's case he did have some use for Cortázar's plot, if not the

full cast.

Both artists share a

sympathy for an occult solution to the mystery of life. Both use the geometry

of art to explore their themes. Both use the surrealist possibility of

conscious and unconscious action. But Antonioni's culture is the art gallery,

whereas Cortázar's is the library. The difference? Exterior versus

interior perceptual processing. With Antonioni, there's always a melancholy

sense of something lost -- and you see this in many of his films -- which is

why he probably identified with Cortázar, who shares the same

sensibility. In both artists, the autobiographical element is always close to

the surface, regardless of the disguise.

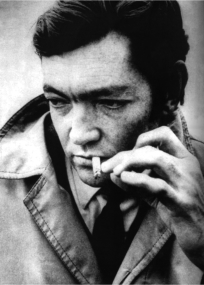

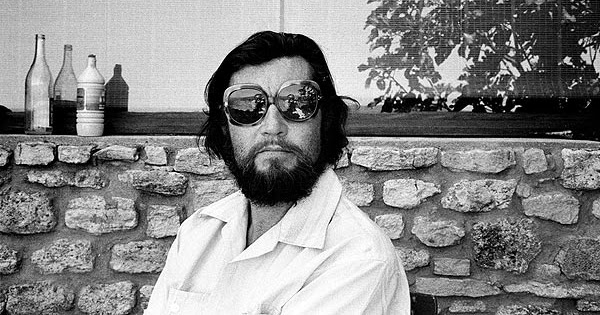

'Roberto Michel,

French-Chilean, translator and in his spare time an amateur photographer...'

Obviously Antonioni could identify with being a photographer. As for

Cortazar... he was Belgian-Argentinian and a translator.

'I don’t like

autobiography. I will never write my memoirs. Autobiographies of others

interest me, of course, but not my own.' (Paris Review)

You can laugh this

off, of course, because what is his famous novel Hopscotch (1963/66) but a

writer's journal jazzed up as fiction: '...here I am a Frenchified Argentinian

(horror of horrors), already beyond the adolescent vogue, the cool, with an

Etes-vous fous? of Rene Crevel anachronistically in my hands, with the

whole body of surrealism in my memory, with the mark of Antonin Artaud in my

pelvis, the Ionisations of Edgar Varese in my ears, with Picasso in my eyes

(but I seem to be a Mondrian, at least that's what I've been told).' [Julio

Cortázar, 21, Hopscotch]

|

|