|

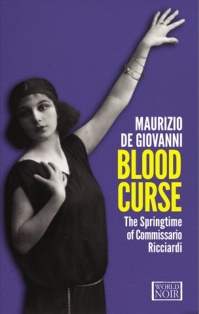

'Luigi Alfredo

Ricciardi, Commmissario of Public Safety in the Mobile Squad of the Regia

Questura, or Royal Police Headquarters, of Naples. The man who saw the

dead'

This cop, this

Commissario Ricciardi, is more like an undertaker who lost his hat passing

through the gates of Hell. While the Neapolitan underclass hates cops, the

people fear him instinctively, as if he's a warlock, can see their shame and

guilt and cheap ambition at a single glance. Of course he's no fascist, just an

orphan aristo who lives with his nanny and plays at being middle-class by

holding a middle-class job. He's the 'New Man' although he holds no party card,

a citizen of the present, lost between the old and the new, forensics and

intuition, formality and poetry. He's a fantasy, as no one so sensitive could

function as a homicide detective; maybe a rogue priest committed to exorcisms

and a formal appreciation of the occult, yes, maybe that... but not a homicide

detective. He's too much of a Stephen King contrivance to be real, yet de

Giovanni gets away with this unlikely casting because Ricciardi's role is

understated within the cast.

Is he the protagonist?

Not really. His Sergeant's story is just as important as his own, if not more

so, and several of the characters have just as much time in the spotlight. You

might think of Ricciardi as being symbolism, a cipher for the poverty and

suffering of the people, a mini Jesus with a mission. Of course he's in love,

and loves from afar, a fugitive voyeur too polite to engage in

foreplay.

'...nor did he pay

attention to the bare-breasted women, who withdrew into the darkness of the

cross-streets as he passed only to reemerge, immediately, offering themselves

to anyone who felt the springtime pulsating in his veins, or who simply felt

loneliness in his heart.'

The novel is more

concerned about setting and characterization than plot, as scenes are often

redundant in terms of advancing the action, although their sociology keeps us

engaged -- manners, mood, and imagery. It all works. The lines, the images, the

sensibility:

'A silence fell

that was as thick as the earth covering a grave'

'So he said, let

her stay home in the dark, since even the sunlight was disqusted at the thought

of touching her'

No one is immune to

this Neapolitan melancholy. Maione the cop -- Ricciardi's sergeant -- has

fallen in love with Filomena precisely because of her disfigurement, as if she

has become a living symbolism of his profession rather than the victim of an

unknown lover.

Ricciardi dislikes

modernism, the new architecture, is 'always moved by the sight of ancient,

noble arches and the delicate friezes that lightly ornamented the massive

marble blocks'. This marks him clearly as a Romantic, a prisoner of the

Sublime.

'Ricciardi couldn't

say exactly why, but he found it somehow more upsetting to think that people

were dying needlessly in the service of ugliness.'

So there it is. One

detects a rebuttal of the new fascist architecture and the brutalist grandeur

of fascist Rome.

Blood Curse is only a

'detective novel' because it has a couple of detectives as characters, not

because it follows the convention of resolving the mystery through the eyes of

the investigator. To be sure, it uses the cheat-narrative method of withholding

information by cutting from the scene, coitus interruptus, although the

emphasis on character and relaying information from each character's

point-of-view make this novel straddle both the mystery and mainstream styles.

That de Giovanni is aware of this, is in revolt against the cliché, is

signalled when Ricciardi's boss lends him a galla (the Italian "yellow"

crime series) detective novel:

'...the good guys

all had Italian names and the bad guys had American names, the women were

blonde and emancipated, and the men were tough and

tenderhearted.'

Ricciardi reads it in

spite of himself, his scorn for the easy propaganda of the pulp genre... yet,

save for the fantasy women and the ethnocentric morality, is it really that

much different from the world he finds himself in? The difference is in the

action, the speed of the sex and violence, the filmic need to make the story

move fast regardless of time and space.

Blood Curse is slow,

almost lazy in its movement. The landscape and its atmosphere predominate, as

if the characters are mere puppets of the Neapolitan spring, infected by a

Lawrencentian blood fever. It's this old-fashioned (or 'traditional') tip

towards literary naturalism that underscores de Giovanni's poetic style, gives

it a calculated sense of pity and mercy towards the characters rather than a

headlong gallop towards the end and the bitter truth so typical of the

crypto-fascist pulp genre. Just as Commissario Ricciardi is antipathetic

towards modernism, so too Maurizio de Giovanni.

The murder at the

heart of it all -- Carmela Calisle, fortune-teller and secret loan-shark, the

malignant Mother Teresa of the Spanish Quarter, kicked to death in her ratty

apartment -- is a clever crime to hinge the action on. The symbolism in it

reflects not only the superstition of the Neapolitan regardless of class but

also the desperation of a society stagnated in poverty and class privilege. The

old lady was a bit of a detective too, it seems, as she used the concierge to

sleuth-out information on her clients and so provide them with uncanny truths

which helped indemnify her predictions. And, of course, her loans to her less

mystical clients.

'In the rotating

succession of Kings, aces and Queens, the old woman read what was fated for

every single day of her life'

So who did it? Emmma

Serra di Arpaja, free spirit noblewoman who drives a little red sports car

(just like Mussolini)? Her husband, the tortured professor and

lawyer?

Or Tonino Iodice, the

pizza man who's stretched his business a little too far for his credit? How

about Don Luigi Costanzo, the neighbourhood camorristi thug who lusts

after the beautiful widow? Bambinella, Brigadier Maione's tout... Nunzia

Petrone, the fortune teller's spy... Romor, the lothario tenor... Gaettano, the

precious Oedipus Rex son of the mutilated one... or Teresa, the peasant maid...

it could be anyone of them. There's no New Age airport mall homogeneity about

this cast, no post-modern uniformity. All is caricature, like potatoes bursting

from the sack.

Get it from Amazon

Canada

|

USA

|

UK

© LR

August 2017

*Check out LR's

OUTLAW

ACADEMIC »»

or LR's novel

RADIO

BRAZIL »»

|