|

Here's the issue:

Cornell Woolrich didn't consider his cloistered world all that interesting.

"This sort of life would be fatal to a writer trying to write realistically,"

he said. So he wrote "entertainments", escapist fiction with a dark edge, where

his doomed characters fall inevitably into the abyss that sits unmapped in the

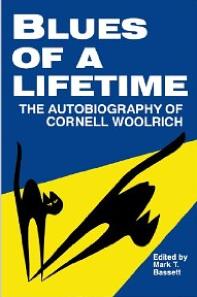

shadows of everyone's mind. Yet Blues of a Lifetime does contain some

Fitzgeraldian flashes of loneliness and pain so that the five episodes do

reveal the measure of the man, how he became a writer, and possibly

why.

Woolrich: exotic

settings (1880s Gold Coast, in his masterpiece Waltz Into Darkness, or

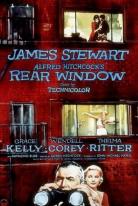

Caribbean, as in Papa Benjamin), voyeurism (Rear Window), low life on the

street (his stories for Detective Fiction Weekly, Black Mask, Ellery Queen's

Mystery Magazine, and other pulps) demarcate his fictional terrain. His mastery

of period jive talk is evident in many of these pulp stories, where the

hard-boiled and the soft collide in criminal stitchups and bizarre blunders.

Innocents are victimized, criminals snake-eyed. In The Dilemma of the Dead Lady

(1936), an American hustler kills a French shop girl, is forced to board an

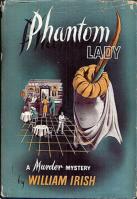

ocean liner at Cherbourg with her body in a trunk. In Phantom Lady (1942) a man

accused of murdering his wife has only one alibi: a mysterious woman no one

seems to remember even though they saw her with him. A cyanide cigarette, a

cyanide tooth filling, a thousand dollar bill cut in two as an invitation to

murder... Black Widows, dope fiends, the falsely accused, good cops, bad

cops... grifters, hoods, burlesque dancers... hotel clerks, doormen,

managers... jazz musicians, voodoo priests, actors and movie queens... Woolrich

has them all, sometimes cheap and sleazy, often homicidal, all willing to roll

the dice for good or evil, even if it means jumping through a seventh storey

window or putting on the mask and getting strapped into the electric chair.

Perhaps the most

interesting metafiction in Blues is II, Poor Girl (Vera), Woolrich's cruelly

poetic recollection of first love. Student falls for a poor girl down the

street, dresses her up, takes her to a party above her social station where she

becomes a hit, a glamour doll everyone wants to be or get. She then disappears

from her boyfriend's life, and he becomes a tragic pariah to her family. In the

end he discovers she's been siphoned into the underworld, the moll of a

faceless hood in a faceless black sedan.

So much for Vera, so

much for the early dream of Woolrich. The bare essence might remind us of

Maugham's Of Human Bondage or any other student love story. The New York

landscape is real, as are the characters; only the ending is suspect, a

romantic masochism in sketchy relief. Women go to Hell in a black car, and boys

are left to become artists.

IV, President

Eisenhower's Speech, is also very good, not only as a story, but also for the

insight it gives us about what life was like living in a Harlem hotel with his

mother. There are two actions -- Eisenhower's address to the Nation on the

radio, and a fire that's coming up the ventilation shaft -- which work as

contrapuntal symbolisms. As a Cold War metaphor or a straight forward account

of Woolrich's concern for his mother, it tells us a lot about the reclusive

writer's psychology. He's a caring man, both for his mother and the colored

lady who lives just down the hall... and perhaps he's a bit like Eisenhower,

concealing the truth in order to sustain a sense of calm.

V, The Maid Who Played

the Races is a late Woolrich tale, based on his days in the Roosevelt Hotel in

Seattle. It's whimsical, uses the old sit-com bromide of the mistaken

assumption or convenient misunderstanding. The room maid thinks he's a jockey,

has inside tips to offer. He goes along with the charade, not wishing to offend

the aged maid, gives her the name of a horse which -- wouldn't you know it --

wins and brings a nice payout for the maid, who is facing retirement. The

strength is in the telling, not the fairytale of a "writer" mistaken as a

"rider".

|