Directed and scripted by David Mackenzie from the novel by Alexander Trocchi. Photography by Giles Nuttgens. Music by David Byrne.

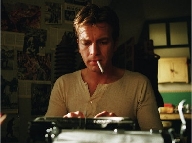

Starring: Ewan McGregor; Tilda Swinton; Emily Mortimer; Peter Mullan. Produced by Jeremy Thomas. Han Way Films/The Recorded Picture Company UK 2003.

Young Adam by Alexander

Trocchi

Olympia Press 1954/Calder Books 2003

"The themes that obsess both modern art and existential philosophy are the alienation and strangeness of man in his world; the contradictoriness, feebleness and contingency of human existence; the central and overwhelming reality of time for man who lost his anchorage in the eternal." (William Barrett, Irrational Man, a Study in Existential Philosophy, 1958)

It's remarkable that this film was made at all, given the UK film industry's slavish compulsion for feeding Hollywood's various expectations of Brit cuteness (Notting Hill, Love Actually, Calendar Girls etc). But producer Jeremy Thomas has a history of backing tricky counter-cultural projects like Cronenberg's Crash and Naked Lunch. Here he's worked (to great effect) with a first-time director to adapt a downbeat existentialist novel by a dead Scot.

Trocchi is often described as a cult novelist, a junk scribe, the Irvine Welsh of the fifties who self-destructed in the eighties amid personal chaos and a clutter of abandoned projects, like Sigma, "the invisible insurrection of a million minds" and the Anti-University of London . But he was also the impresario of the defining British alt.culture event of the sixties: the 1965 Albert Hall Poetry International

I'd got a fast furious hitch from Oxford with a businessman in a Jag who had problems with his factory and his marriage. "My wife won't sleep with me any more," he growled, overtaking three Morris Minors in the wrong lane. Iain Stewart met me at South Ken tube. He was there to hail Ferlinghetti and the birth of a pop poetry . Willy Kay (he's a sort of vicar now) was expecting Keatsian raptures. High in the tiers we could only glimpse a beaky profile of MC Trocchi down there on the flower-strewn promenade, where a fey girl in a white dress undulated to the chime of Ginsberg's finger-cymbals. Trocchi was a dark presence, a mere continuity announcer or so we thought. We didn't know that the whole event had been dreamed up in Trocchi's flat, that he'd expected five hundred people rather than eight thousand of us. We were more focussed on the ominous drone of the Burroughs basement tapes, the joyous roar of sound poems by Ernst Jandl, Pete Brown and Mike Horovitz, Edwin Morgan's space chant, Adrian Mitchell's ranting for peace, Harry Fainlight's ode to the spider-god of lysergic acid. And we were all waiting for Ginsberg to Howl; and he told us to Be Kind, for this was the dawn of New Albion, our quest to recover our Blakean pre-Adamite Innocence....

Trocchi was definitely Experienced, a post-Adamite Beat. The book had been published over a decade earlier, initially under Maurice Girodias's Parisian erotica imprint, the Traveller's Companion series. " Ten publishers have turned Young Adam down and I'm going to dirty it up," he told Christopher Logue, another Albert Hall survivor, back in 1953. Sex as desperation certainly drives the narrative, even in the later editions where Trocchi had cut back the number of copulations. Yet there are complex sub-texts about guilt, dread, denial, and the flux of identity in a world of random events, revealed in an intricate mosaic of flashbacks. David McKenzie's achievement is to transform the nuances of this first -person narrative into cinema.

We're in austerity-age fifties Scotland, evoked with eloquent bleakness through Giles Nuttgen's photography. In the opening sequence the camera takes us on a long dive into deep murky water - the underside of a swan, industrial detritus of a canal bed, imagery of flow and decay. Ewan McGregor plays Joe Taylor, a young drop-out with literary aspirations, who's taken a job as mate on a rusty barge plying between Glasgow and Edinburgh. With his boss Les (Peter Mullan) he drags the corpse of a young woman out of the canal,. She's almost nude in a muddy petticoat. His flinching half-caress on the nape of her neck and his uneasy eyes suggest a connection with the dead girl.

But Joe also casts a bold eye on Les's wife Ella (Tilda Swinton) , who's driven by low-key sexual frustration and barely-repressed fury with her complacent husband. Soon Joe is fondling her inner thigh under the breakfast table. While Les sits in the pub with his cronies, eagerly discussing the erotic enigma of the drowning and possible fame in the local press, Joe kneels in the shadows of the tow-path with his head between Ella's thighs. This is sensuality in the raw disconnected moment, as a port to self-forgetting, transmitted brilliantly throughout the film via McGregor's subtle shifts from feral intensity to blank disengagement.

It becomes clear that Joe has much to forget -- like the recurrent image of a white leg trailing from a stretcher. His relationship with Ella is reinforced, quite literally, by accident -- Ella's young son Jim falls overboard and Joe instantly dives in to rescue him. It's a brave impulse that obviously raises his standing with Ella -- but it's foreshadowing (in screen time) another immersion that is already deep in Joe's back-story.

As the barge crawls back and forth, and Jim is sent off to stay with her cousin Gwendolen, Joe's sexual adventures become ever riskier. They couple in the cabin while Les stands (literally) overhead, on deck at the wheel. But this voyage to inevitable disaster is intercut with apparently random flashbacks of Joe's affair with bright young middle-class Cathie (Emily Mortimer). Her office job supports him in his attempts to write, a bohemian tenement idyll that disintegrates when his creative frustrations as an Outsider collide with her impatience and disillusion. In an explosive encounter that recalls Last Tango in Paris he smears her with food as he straddles and penetrates her, a furious but joyless orgy, like a porno take on a sixties Happening.

In fact throughout the film MacKenzie's direction and Nuttgen's photography recreate a vision implicit in Trocchi's narrative resonances and image-patterns, a vision of what Barrett called "porous contingency," the sheer messy physicality and unpredictability of existence. Perhaps a kind of dark Presbyterian existentialism, where the self-forgetting of sex is merely a prelude to decay and self-obliteration. It's epitomised in a close-up of a fly crawling across Ella's nipple, or in the Joe's last rough fuck with Cathie, glimpsed between the undergear of a dock side rail wagon as they roll in coal-dust and oil.

And it's purely accidental that Cathie, now pregnant, stunned by Joe's post-coital rejection, stumbles over the edge of the dock and falls. This is the carnal knowledge that Joe can't get out of his mind as random events spiral out of his control. When Les leaves Ella begins talking about marriage and a nice bungalow. Ella's blowsy cousin Gwendolen is widowed and soon Joe, half-repelled but randomly compelled, is mechanically shagging her in the alley - an act which terminates his relationship with Ella and his life on the barge. A casual acquaintance of Cathie's, a plumber called Gordon (perhaps wisely changed from Goon in the novel) is fingered for her murder on purely circumstantial evidence. Joe finds himself in the public gallery of a court-room witnessing a man being ritually condemned. He listens to the absurd rhetoric of the prosecutors with the same sense of unreality that the anti-hero Meursault feels in Camus' L'Etranger watching the process of his own murder trial. He sends a futile, almost perfunctory anonymous message to the court but he doesn't make the grand confessional sacrifice that might save Gordon from the hangman. No Hollywood redemption plots here.

In any novel the internalised voice is difficult to convey on the screen without noir-ish off-screen monologues, a device which McKenzie's script avoids. It's particularly true of Trocchi's writing. Like Sartre's anti-hero in La Nausee , Joe is hypnotised by the very fact of physically being-in-the-world and yet estranged from it,. The writing carries a increasing sense of displacement and unreality as the consequences of Cathie's death play out in the court room. "I tried to make myself comfortable on the seat, looked closely at the polished wood; my legs were tired and that made me look at the scarred black leather of my boots. In a way I was bored, I hasn't realised how utterly dependent on things I had become, even if only to catalogue them, saying over and over again, the door, the seats, the boots, the mirror, the thing to wash in..." McKenzie's alert direction and Ewan McGregor's performance externalise the increasingly uneasy angst. The ending opens on to a void; and Joe drifts on....

The new Adamites wander out of the Albert Hall and mill around on the pavement. "Go back to your homes - if you have any..." shout the exasperated stewards. We didn't realise there were so many people in England with such long hair. And we're so bedazzled by the regiments of flower maidens that we can't find the funk to speak to any of them. It might not be cool. Ginsberg, Trocchi, Logue and all have been spirited away to a secret party in paradise, or so we believe. Our vague project of interviewing them fizzles out. So we stagger back to a floor in someone's flat, still arguing. Willy can't make any connection , for Heaven's sake, between Shelley and Ginsberg. Iain says poets gonna be the new Beatles. Brother Paul, all bearded and weedy, keeps hearing Burroughs' dark murmur. Trocchi's big night has given us a taste of a new Knowledge.

© Paul A. Green 5/04