|

burned by love,

yet loves to burn

No doubt some people

will find Behzat Ç too vulgar and too graphic in its scenes of torture

and murder and general human anguish. Man's inhumanity to man (and woman and

child) seems to be pushed well beyond the usual limits into a new kind of shock

theatre. The photo naturalism becomes voyeurism. Chic downtown villains shoot

victims between the eyes with sleek 9 millimeters as easily as blowing kisses

and hi-life/low-life women knife enemies as easily as preparing a meal. Behzat

Ç is violent alright and some will dismiss it as nothing more than a

soap opera of death, too absurd to be taken seriously... or simply the folly of

another 3rd World society pretending to be 1st World. The cheap sensationalism

of homicide a la mode reduces human behaviour to a sick tango of sexy

sadism and religious masochism. Predators, suckers, guns, knives... HGTV condos

and open sewers, trendy clubs, cafes and hillside cemeteries. Sounds like

Europe or the US, you think. You sigh, think, do I join in with some sanctions

against the Ankara government or do I retire to Turkey, buy a jug of

raki, and enjoy the ride?

So, in the end, is

Behzat Ç little more than a commercial for this nihilist anti-social

behaviour? Even Behzat himself sets a rotten example with his bullying,

pro-active violence and lousy manners. He doesn't wear a uniform, dresses like

a hood, drinks on the job, commits crime to solve crime, carries a badge yet

operates like a gangster. If he wasn't protected by his boss and powerful,

unseen people, he would be behind bars himself or prowling the sea-wall of some

castellated mental home like Hamlet crying the midnight blues. Yes, Behzat

suffers, and it's his suffering that allows us to see past his folly. He's a

victim par excellence, a patsy, another rat in the prison lab of human

existence. But he fights -- between the hangovers and the murders, he fights

with a feral cunning, and even when the truth is killing, he forgives,

survives, retains compassion, never surrenders completely to the dark side even

though he wears a black leather coat.

Behzat. Burned by

love, yet loves to burn.

"Suffer," he tells

Harun, his deputy, when Harun goes into meltdown over Larissa, the grifter

Ukrainian honeytrap. Or on another occasion, during the final showdown with

Captain Suna, the hyper-feminist killer cop, when she cries, "But Behzat you

torture people!", Behzat replies, "Yes, but I never kill them." While the

nuances of legitimate versus illegitimate violence might seem ridiculous here

because the degrees of moral separation get lost in the melodrama, the fact

remains that Behzat absorbs more violence than he dishes out, and his personal

suffering acts as a moral barometer in the game of right and wrong.

Even though he's a

mess, Behzat functions quite well, just like Robocop, injured on the inside but

rockin' on the outside. He's all business, a man of few words, preferring an

Esperanto of grunts and curses, body feints and eye flashes over talk. He's so

economical with language that he hangs up, or walks out rather than says

goodbye or hello baby. This is especially true of the first season, when he's

driven by the need to find his daughter's killer; by Season 2, you see a

gradual softening in his manner (and that of his team), as if the government

has told the producers of Behzat Ç that they'll shut the series down if

they don't present the police in less fascist way... or perhaps it's just the

script writers introducing political correctness into the scenario. There is a

decided movement from the killer as evil to the killer as victim as the

episodes pile up and the plotting moves inward. This is good, as it confirms

humanity in a rather inhuman landscape. Not for nothing is Behzat stuck in a

loop of predator and prey, symbolized by the wildlife documentaries he watches

at home as he drinks himself into a stupor on his down-market suede throne.

He frequently sleeps

where he passes out, fully-clothed, fully bohemian. In truth, Behzat is more

like an artist than a detective, bucking convention as he does, living in

fashionable squalor (his house is furnished like a cheap motel, its generic

indifference at once anti-materialist and personal), yet seeking beauty as

beauty is the only reason to continue living. He craves the female touch like a

wild dog who can only settle down when stroked by a magic hand. Yet you do

wonder if in fact Behzat is just another in a long line of Turkish bullies who

use corporal punishment and violence to extract a confession just for the sheer

pleasure of it. Just because he looks cute with his boy hippy haircut and

western desperado moustache and dangling prayer beads doesn't mean he's a 21st

Century liberal hep cat. For those of us who live further west, his

swash-buckling slouch and strut is a manner we admire, a style we all harbour

when we're tired of voting and nothing gets done. Behzat gets things done. He

might be rough, but he's honest, and if he punches a woman in the face, well

it's an honest mistake. Lawyers exist, but they only exist to clean up the

mess. In fact, by Season 2, he marries a lawyer, the Public Prosecutor Esra,

and she cleans up his mess, although she pays dearly for it.

The Freudian nightmare

that is his life deepens like an ancient hereditary wound, echoing Oedipus or

Lear or any doomed tragic hero whose misery transmits through the ages in

dreams and in the genes of the deranged. When Behzat is remanded to a mental

hospital following the suicide of his undergraduate daughter Berna -- actually

murdered, although he doesn't know this yet -- fate delivers to him a new

daughter, Süle, who becomes his saviour... and then, like a poisoned

chocolate, returns him to the abyss once again. An unknown child from an old

flame -- herself a suicide because of Behzat -- who in turn murders her

half-sister in a jealous attempt to usurp this 'woman' in Behzat's life. It's

tabloid, like anthrax in the mail... or UFOs seen through the windshield: he

wants to believe but somehow the lies keeping coming.

He has conversations

with multiple selves -- five, typically, like stand-ins for the five members of

his squad. His old friend Tekin is murdered -- bad enough, but when he learns

that Tekin had been corrupted by the gangsters who seem to control the higher

echelons of the police and the judiciary, even worse. Hope fades like a bad

screw.

Strangely -- or

perhaps typically -- Behzat is the centre of the universe. His squad waits

anxiously for his arrival, stand up when he enters, and even after hours, can't

drink too long without him. Even the arch-villain Escrüment Çozer

doesn't want to live without him, even though this prick cop has screwed his

business schemes, vanity murders, and sex life, has forced him into exile for a

period, even though he's the only one who seems to have the answers to Behzat's

problems. He knows who murdered Berna, he knows Behzat's mother is alive and

scheming, he knows who the bent officials are and the lines of corruption in

Ankara... this chameleon criminal knows all this as the voice inside a madman's

head knows, he knows, he knows, he knows what Behzat needs to know. Therefore

it's no surprise that by Season 3 Escrüment decides to "collaborate" with

Behzat, especially when it comes to finding out who ordered Esra's killing.

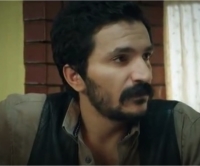

As a character,

Escüment Çözer starts out real, but as his outrageous killing

spree (mostly matters of "disrespect") in defence of his sex life and business

operations gets out-of-hand, his believability is only sustained by

photography. It's the cine and film editing that makes us cringe and thrill to

his master criminal agility, not the psychological portraiture. As a disco

Cassanova with a 9 millimeter and a nuclear credit card, he's acted to

perfection by Nejat Isler. The smile, the earrings, the up-market cars,

the wine, the coke, the babes, the lackies ready to clean up his mess, a

helicopter hovering nearby... sociopath, psychopath, anthropath... an Anatolian

thug with a jet-set life-style, happy in Istanbul, unhappy in Ankara... except

when he's messing with Behzat. As imagery, he provides comic relief from the

grim social realism of the working class murders, student riots, Gulen lefty

protests, robberies and domestic miseries. When he screws on his silencer to

take care of business, you might think (briefly) of the need for more gun

control, but more likely you're left thinking how easy it is to die at the whim

of some jerkoff who takes offence too easily. Escrüment Ç isn't a

character -- he's Death. He never had a childhood, never had a family, just

arrives, fully-formed and goes about his dirty business. You cut finger-nails,

EC cuts people. Behzat hunts killers, EC... hunts.

He's not alone. He has

a pal, a minder of sorts, another hitman in the employment of the Circle.

Basgan Memduh. You might think of Danny Devito when this guy arrives. He's

bigger, although not by much. Less funny, although not by much. He loves to

eat, worries about his weight, reminisces about his time as a special ops

commando eating snakes in the mountains. He shoots people too, and when EC is

in hiding or in exile, acts as an understudy. You're not quite sure if he's a

partner in equal standing with EC or if he's actually his handler, someone who

checks EC's excesses and supervises his escapes. The "Duck Man" tries to

eliminate him but somehow it's Memduh who eliminates the Duck Man. You're not

quite convinced by this scene beside the lake -- the razzle-dazzle gunplay

depends too much on camera editing rather than real action -- although you hang

in there for the laugh and because Memduh has become quite endearing... like a

favorite dog who shouldn't be killing the bunnies, but it's in his nature, so

what can you do? |

A pack of feral dogs

is briefly illuminated by a streetlight, cross the highway ramp after a vehicle

passes, disappear into the shadows on the hunt for food. In a condo, a man

'murders' his sex doll, and the day of Harun's wedding to a traditionalist girl

chosen by his parents, Ankara goes nuts with violence and murder. Man with a

shotgun shoots up a cafe, while another man knifes his wife after he dreams she

was unfaithful... and once again Ghost gets involved with a murderess.

A traffic cop

moonlights as a cartel sniper. A hitman whines about his weight. A kid kills

his grandpa with a pen. Etc.

Aristotle says "Drama

is an imitation of an action". Today, the media feed-back loop accelerates the

emotional need to imitate anything, including the imitation. Despite the moral

imperative invariably contained in endings and exits, sex and death remain the

most imitated events.

Nejat Isler as

the disco cassanova business man Escrument Cozer

Esra,

Prosecutor and Behzat's second wife

|