|

Music & Noise: Lawrence Russell | ¶ Culture Court ¶ |

|

'The desire to return to chaos rises incessantly' [Octavio Paz] § Where and when does electronic music begin? Where does it end... or is it possible it can never end, as it's running through the universe in the endless radio roar of the stars? Luigi Russolo (1883-1947), who has the same initials as me, but looks nothing like me, might be Mile 1 on the highway, if not zero. He wrote a great little Futurist manifesto in 1913 called The Art of Noises (L'Arte dei rumori) which starts with the premise that before machines, there was no sound except for those from occasional natural events. By the Middle Ages there were chants, then chords, and as the sound of machinery intensified, polyphony. This also occasions a move away from the Pythagorean sweet tone into dissonance, which would unravel the complexity of noise. Needless to say he advised "Futurist musicians" to ditch the traditional instruments by inventing new ones that would capture the diverse rhythms of noise. |

|

|

|

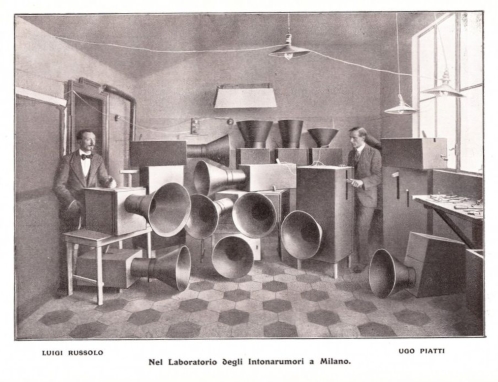

This sounds like a command for the invention of the electric guitar and the polyphonic synthesizer to me. But while he was waiting, he teamed up with the Godfather of Futurism, Marinetti, constructed a few hand-cranked noise machines with horns with Ugo Piatti and staged the first intonnarumori concert in 1914 which apparently ended in a riot. Given the titles of the four "compositions" played, a riot would fit right in with Russolo's noise-music aesthetic and the Futurist declamation that "war is the only hygiene of the world". Russolo was a reactionary, tired of the old orchestrations which sought to emulate the sound of the pastoral before the pastoral surrendered to industrialization. The Futurists liked the mathematical magic of machines, the geometry of the future, not the accident of the past. While his instruments were as crude as a miller's wheel, their primitivism was an atonal assertion of the fundamental laws of gravity. Thus he thought in terms of noise networks: Awakening of a City... Meeting of cars and aeroplanes... Dining on the terrace of the Casino... Skirmish in the oasis, etc. If the tape recorder had been invented earlier, perhaps Russolo's simulations would've been unnecessary. Yet the fundamentalism of the exercise was at attempt at reeducation within the existing dialectic of stage, orchestra, and listener. Unfortunately the rise and fall of Fascism led to Futurism's partial disgrace due to the political aspirations of some of its proponents... yet when you think of the real-time films of Andy Warhol like Sleep (1963, 5hrs 20 mins) or Empire (1964, 8hrs 5 mins) where the visual "noise" is purged to its documentary essential, what is this but a Futurist reeducation exercise? In Warhol's case, voyeurism and narcissism replace the politics, but as in Russolo's case, the "action" of the artist is the historical marker, not the art itself. Another opponent of the twelve tone scale was the Russian composer Arseny Avraamov (1886-1944) who went big time symphonic with his Symphony of Factory Sirens -- perhaps the first piece of environmental art outside of monumental sculpture -- wherein he used not only factory sirens and automobile horns, but also the ship horns and artillery of the Russian Navy stationed at Baku on the Caspian Sea. This was orchestrated noise in real time, a political statement in honour of the Soviet as much as it was artistic. But this was only one part of his devolution from the concert hall -- "graphical music" was the other. Avraamov was part of a group working on an early synchronous sound film who noticed the visual pattern on the optical strip, wondered if "art" was rendered on the strip might it not produce a new form of music (it was even speculated that if they used Egyptian images these might reveal a lost language, the music of the ancients). This sort of ornamental pattern music was also being developed at the same time by a couple of Germans, Rudolpf Phenninger and Oskar Fischinger. As with the invention of photography, technological invention appears independently in two or more places at once. Many people think electronic music started with the soundtrack for Forbidden Planet (1956), composed and recorded by Louis and Bebe Barron, although the film industry had been using Tesla's Theremin for a number of years for its spooky beyond-the-grave feel. But the Barrons went way beyond that. They overloaded a ring modulator circuit, and, using a two recorder loop feeding into a third, came up with the soundtrack. This technique of "misuse" and "accident" is the improvisational root of early electronic music. Louis Barron built a number of oscillators -- sawtooth, square and sine wave -- which you'll find in all of today's synthesizers. It's interesting to note that the Barrons recorded a number of famous authors in their Greenwich Village studio, including Aldous Huxley, Henry Miller and Anais Nin, thus anticipating audio lit. These red vinyl pressings must be worth a fortune on the collectors' market today. In actuality, it's the Barron's soundtrack for Ian Hugo's short film The Bells of Atlantis (1952) that might be the first applied electronic music. Hugo was Anais Nin's husband, and you can hear her as the "Queen of Atlantis" reciting her story against Hugo's expressionist montage, which predates anything done in the sixties by the "Expanded Cinema" crowd. You can find this short film on the internet. John Cage was one of the first composers to use the Barrons' studio. In 1953 he created Williams Mix, which was for live performance using eight different tapes. The concept sounds very similar to Luigi Russolo's intonnarumori concert in its desire to simulate environmental noise in order to establish a pattern of proto-music. It's an eclectic montage of real sounds, tape flutter, tape speed manipulation, azimuthal jitter and so on... and is quite an impressive soundscape, because, while there's no beat pattern per se, it appears to be "cut to the beat"... and the use of eight playback machines achieves spacialization in the era of the monaural broadcast, albeit in a theatre setting. In parallel to the Barrons is Daphne Oram (1925-2003) who got into electronic composition while working as a junior recording engineer at the BBC in the 1940s. While she used the musique concrete approach -- the manipulation of natural sounds -- she also followed the Russian example of drawing on blank optical film, which was a way of translating pictures into sound. She built a composer which ran ten strips of 35 mm film that enabled quite a sophisticated level of control, and in some ways resembled the Russian ANS optical synthesizer developed by Evgeny Murzin. Her "Oramics" compositions were used in UK television and film throughout the fifties and sixties, i.e. the 1957 BBC production of Amphitryon 38 by the French dramatist Jean Giradoux, and Jack Clayton's horror film The Innocents (1961). She also used a sine wave oscillator and built her own studio in a cottage on the south coast of England, as she wasn't getting enough respect at the BBC. While her work was sublimated as commercial ephemera, she was in fact the Agatha Christie of audio art -- persistent, prolific and more popular than you would suspect. Another realization of the Russolo noise-music aesthetic was Pierre Schaeffer's musique concrete exploration of radiophonics and the electroacoustic possibilities of recording. He came up with the term musique concrete, initiated the revolt against notation as a form of scripting. Bag traditional instruments, collect sounds, mine time and space. You could say the only difference between Russolo and Schaeffer is a tape recorder. Musique concrete is/was the realization of the ideas first expressed in Russolo's The Art of Noises, and led to the electrification of European classical music, and the de facto dematerialization of the concert hall shell in order to include the sound of the world outside. It's a movement from fiction to documentary, and you see it in all the arts as recording replaces the mnemonic need for scripting. It should be noted that the Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu claimed that he experimented in eletroacoustic recording similar to Schaeffer's around the same time, i.e. Static Relief, 1956. Messiaen... Boulez... Barraque... Varese... Stockhausen... Xenakis... Honegger... all of these now well-known composers studied and hung out at Schaeffer's Musique Concrete Research Group in Paris in the 1950s. It doesn't take a genius to recognize that electronic music had arrived and all that remained was for the development of the polyphonic synthesizer to finalize the triumph of noise over tone. Was this a good thing? Did the absense of technical limitations lead to a decline of compositional imagination? Is it an art anymore when a fist on the keyboard can produce the music of the spheres? Has culture been handed to the scientists, the people who write the algorithms, manufacture the machines? There's certainly a lot of delusion when an artist stands between an accident and an oscillator and thinks he's sexy... and even more when the crowd thinks so too. It becomes more and more difficult to distinguish between the fiction of the player and the documentary of the machine. The artist rises, opens the curtains and sunlight pours into the room, and by the time night returns it doesn't matter if he's alive or dead as the sun will return with or without him. © Lawrence Russell (first published in Outlaw Academic, Feb 2016) «« CC Audio |

CC Audio | © 1998-2025 | Lawrence Russell