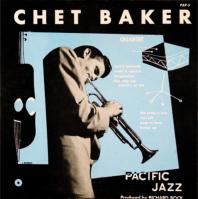

and introducing Chet Baker and his Trumpet

ƒƒ Chet Baker -- what a paradox. Gentle, playful, loving, hard-working some of the time; cruel, self-centred, lazy and downright ugly a lot of the time. This could be anyone, of course, as moral frailty and creative expression are a wedded contradiction, and the occasionally-famous are seldom allowed private ugliness. Drugs, addiction, women and cars -- his crimes were all secular, even though these things drove the omnivorous industrial dynamic of American free enterprize, and as a jazz hipster junkie longing to be free, his persecution was part of the corporate cultural lie. Perhaps. Perhaps true freedom always requires some sort of enslavement.

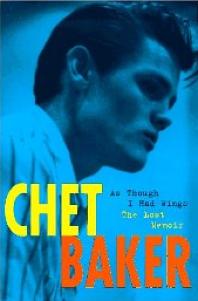

He had the Hollywood look that fitted his time -- the 40s, the 50s, maybe the 60s -- the sort of falsely innocent face that looked good on an album cover, the sweet white beauty of post-war American triumphalism. Indeed, Hollywood called, gave him a small part in the 1955 Korean war movie Hell's Horizon. In the credits he's listed as: "and introducing Chet Baker and his Trumpet", as if the trumpet personified a ventriloquist's dummy. He plays close to character, a B-29 airman called "Jockey" who lies around in the crew tent blowing pensive figures on his horn. Acting? Not really. A few jive talk lines and he gets to die. Following a fatal mission to the Manchurian border and a belly landing back in Okinawa, his skinny body is recovered from the burning wreck and laid out on the runway; one of the crew finds his trumpet mouthpiece, tucks it below his crossed hands... up violins as the crew walk away and that's it for Hollywood and Chet Baker. It was a 10 day shoot, fast even by B-movie standards, yet Chet says he "got really bored" hanging around waiting for his scenes. Truth is, his voice was all wrong, too high and androgynous for any male lead, so he could only be a bit player, a parody of himself.

But this didn't mean he couldn't live like a movie...

Los Angeles, summer of '57. Corner of Hollywood Boulevard and Western. The Hipster arrives late for a gig at the Peacock Lane Club, parks across the street, sees the cops under a streetlight checking for crucifixion marks. Two friends, users, their arms outstretched and gleaming. The Hipster slips into the club, recovers his trumpet, follows the shadows back to his car where his young wife is waiting. She's seven months pregnant, shows it, is anxious. The Hipster slips into first gear, pulls away softly, then spots a black unmarked Ford coming at him. He guns it, hangs a left, then another. He's driving kinetic, getting low yo-yo like the Red Baron, soon loses the eyeless narc, makes the freeway. He stops at the ramp, gives his wife some dough for a cab home. She gets out, and he breaks west for Newport Beach.

Cut To: the Hipster's 1955 XK 140 Jaguar sports slipping through the pre-dawn luminosity. The Hipster likes sports cars, will always like them, blew some savings that was owed to the taxman for this one. Well it's cool, flies like Bird, the great Charlie Parker who made him a bop disciple. Low deco streamlined chariot of the damned. He has a taste for the European, acquired during his US Army bugle-boy days in Germany. Jags go good in SoCal. Mike Hammer drives one in Kiss Me Deadly, and what's good for Hammer is good for Chet Baker, junkie hipster, winner of the 1954 Downbeat poll for Best Jazz Trumpet.

Check out his features: yes, he could be in the movies. He has the 50's chiselled jaw, cheek bumps, surfer wave hair, the SoCal cool. He could be Ralph Meeker playing Mike Hammer, although he's a ringer for Chuck Connors, The Rifleman... a handsome skull with eyes. Too bad he's an outlaw. Too bad he shoots it in his arm. Too bad 'cause he's white and Miles Davis is black and America still wants white. Cops don't care, though. They'll hunt anything, especially junkies, especially jazz junkies. They'll hunt the lizard and the lizard knows he's gotta head for the ocean.

Chet has a friend across the bridge in Balboa, where all the fishing boats hang up. Bobby's just heading out to harvest abalone in the Santa Barbara Channel, off San Miguel Island, so Chet decides "to cool it for a while, to clean up and let the sun work on my arms". After four days, he starts to feel better, get a little sleep. Meanwhile his friend Bobby is doing the bottom crawl, a hundred feet down, bagging the abalone, sending it up top on the electric lag line. Ten, maybe twelve dozen primo pinks every dive. Easy. No great whites around and the sea lions are cooling it on the rocks. Time for the Hipster to solo. Sea birds are dropping from the sky like footballs, using their wings to propel themselves deep underwater to snatch some fish. California Murres, smarter than penguins, faster than humans, hip as D Dorian. Yep, time to drop from the ladder, break the surface, play a little below the centre of tonality.

Well, he's done lots of diving before, skin and Aqua-Lung, but never any air-line stuff. Suit, helmet, lead boots. Down he goes, feet first, following the bag line, down, down into the undulating sea-weed forest... he starts walking around, gets lost, and his feet are getting colder. The suit is leaking, the water is up to his chest... he's been going in the wrong direction, doubled back on his air-line, just like he's gotten lost during a horn solo, can't find the point of resolution, very uncool and something he never does unless way too stoned and then some. But down here, hiding from the Man, doing the lizard but not doing it right, he's in trouble.

Yeah, let's get lost.