End of the Hippie

Era

During the seventies

Brown continued writing with Jack Bruce, while diversifying into A & R work

for Deram, Decca’s ‘hip’ subsidiary. His personal life had

diversified too, involving children from previous relationships and a long-term

relationship with Sue that was becoming problematic, owing to ‘ a greed

for new places and faces, something that took a long time to control.’

The new places

included the Hyatt House in Los Angeles, where Led Zeppelin had ridden

motorbikes around the corridors. Brown had been tasked to work on Bruce’s

album ‘ Out of the Storm’ at the Record Plant. But ‘there was an

end-of-hippie era desperate party atmosphere permeating the place which

undermined the work with drugs.’ Only Stevie Wonder in the studio next

door seemed immune. Indeed, Malcolm Cecil, the UK synth pioneer who was

producing Stevie, offered Pete the opportunity to write for him. Pete refrained

because of his loyalty to Jack, then going through a narcotics crisis. It

remains one of rock’s alternative histories, in parallel with another

recurrent theme of the book, intriguing unreleased albums, like the big band

jazz tracks that Mick Jagger was putting down in another part of the building.

The Bruce album was eventually completed in the UK, despite Pete and Jack

nearly drowning in a boating accident off the Aran Isles.

After the demise of

another short-lived band, The Flying Tigers, he made more American trips. A

meeting with Martin Scorcese, fortuitously a Cream fan, planted the notion of

screen-writing, but he was still trying to cope with the excesses of the music

business, exemplified by Ike Turner. ‘ There was a small ante-room before

you got to his flat, where a tray of coke came out of the wall electronically,

and you had to partake before he let you in.’ Another celebrated paranoiac

was Sly Stone, who kept panthers and crocodiles on the premises to deter

unwanted visitors.

Back in the UK by

1977, Pete put together another group, Back to Front, but the scene was

changing. Record executives started telling him that his jazz-tinged music with

its fondness for complex time structures and elliptical lyrics was dead in the

water. Punk had arrived. The critical consensus about punk, expressed by

writers like Jon Savage in ‘England’s Dreaming’, is that it was

a spontaneous grass-roots phenomenon created by alienated working class youth

who felt socially marginalized and excluded from the music industry. Brown

however inverts the paradigm and sees it as a cynical strategy devised by the

music industry – and the fashion business – to exploit desperate

unemployed ‘scab labour’ and/or create fake working class bands

‘to invoke the sympathy of wealthier middle class punters’, betraying

skill and talent in the process. It’s an interpretation that fits very

neatly with the self-proclaimed nihilism of Malcolm McClaren and his

protégé/victim Sid Vicious or the irony of Joe Strummer’s

public-school background. One could also argue that the chaos of punk also

created opportunities for new talents to emerge but that would have cut little

ice with Pete at the time, who decided to make a strategic retreat and try

writing for the screen for a while.

Road of Cobras

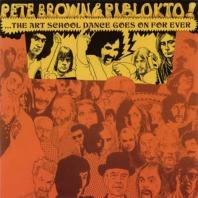

From the eighties to

the present, Pete’s career has continued on its picaresque way, veering

between cult acclaim and obscurity, random affluence and sudden fiscal crisis.

Film credits have included the animated ‘Felix the Cat’ and the BBC

TV drama ‘Railhouse Jock’, commissioned but never transmitted .

Indeed many projects, like a documentary drama about Glaswegian rocker Alex

Harvey, remain in development limbo. However he’s produced outstanding

albums with ex-Bond saxophonist Dick Heckstall-Smith (now sadly dead), with

Peter Green, Rory Gallagher (dead) and many others, often contributing as

percussionist. There’s been a band, the Interociters – named after

the alien machine in the old sci-fi classic ‘This Island Earth’ - and

an ongoing partnership with keyboardist Phil Ryan, which recently produced the

album ‘Road of Cobras’, an apt metaphor for the human condition,

especially in the music business. Having survived a cancer scare and a heart

by-pass, he’s still ready for the road and even does poetry readings.

Many books have

exhumed the counter-culture of the sixties and the rock demi-monde, like the

memoirs of Barry Miles. What makes ‘White Rooms’ so enjoyable is the

vivid recall, the candour and the energy. To quote one of his favourite blues

singers, Screaming Jay Hawkins: ‘ I don’t care if you don’t want

me, I’m yours...’

Paul A. Green

January 2012

««

MEDIA

COURT |

|