Check the files and you'll find my previous convictions re Iain Sinclair's work. This author has notorious form. It's enfolded me over the decades like sweaty sheets entangling the victim of an M.R James tale.

Time is/was a quantum bump on the Ratcliffe Highway as Sinclair's earlier golems stalk the gangland turfs of East London or track the nodes of power linking London, Oxford and Cambridge. Luminous membranes of false remembrance thicken around the reader as the plots curdle. Fiction, documentation and autobiography elide in the twilight.

The town of books. Two

years serfing for the Poet and his White Witch, sorting their used Penguins,

mis-cataloguing Welsh Druid antiquities, haggling with the seedy runners,

divining the gold in their boxes of rubbish, soothing anxious businessmen in

their lust for for Noddy books, bowing before rich Japanese collectors, massive

as Sumo wrestlers, who scooped up whole cases of first-editions, the rare

Dryden, the signed and annotated Ezra Pound..."nice books... very nice books...

knowledge, sir, is the only elegance..."

The town of books. Two

years serfing for the Poet and his White Witch, sorting their used Penguins,

mis-cataloguing Welsh Druid antiquities, haggling with the seedy runners,

divining the gold in their boxes of rubbish, soothing anxious businessmen in

their lust for for Noddy books, bowing before rich Japanese collectors, massive

as Sumo wrestlers, who scooped up whole cases of first-editions, the rare

Dryden, the signed and annotated Ezra Pound..."nice books... very nice books...

knowledge, sir, is the only elegance..."

And later, when my tendons had cracked under the weight of the dead Penguins, and the shop died, I was sorting used library books for three quid an hour in a shed on a pig farm, into categories defined by my cunning new employer - thick romance, thin romance, thick crime, thin crime and so on. Until I got fired for my presumptuous Eng Lit knowledge.

And always, Hay's diurnal round, the mad street people, the daily greeting from dear old Betty ("fuck off back to London with your whore ") the frequent vision of neighbourly Nuscha, a plump Algerian inexplicably marooned in Hay, disrupting funerals by dancing naked in the churchyard. The shopkeepers thrive on their used word-hoards, harvesting their obsessions - bee-keeping, Croatian nationalism, Edwardian porn, leather bindings by the yard, commodity fetishism gone bonking mad.

Meanwhile Geoffrey the Scholar barely survives by peddling the battered ornaments of his learning , editing obscure fragments of military biography. Every noon he's compelled to stagger around High Town searching for "sound men" who can share sherry and his Augustan world picture. "Sir, this town is full of knaves and lunatics..." Sinclair got it right when he quoted the poet Anne Stevenson: "The town is full of people who have limped this far and don't have the strength to limp any further..."

Underlying the whole scenario, the incessant rhythms of intrigue: Richard Booth, King of Hay, Emperor of the Tomes, who turned every other structure in the town into a book shop, issues fiats and fatwas from his half-ruined castle against arch-rival entrepreneur Leon Morelli, who won't stop plotting parking lots, heritage attractions, business parks in a desperate attempt to sanitise this anarchic fiefdom.

On the surface there's grotesque contemporary satire, populated by rascally book-runners, obsessive deadbeat poets, conniving media drones, dodgy politicians, evoked in language so rich you can almost smell them.

But dig deeper. Get paranoic-critical in the Dalinian mode, finger the dirt of the earth mystery. Then Sinclair's texts - White Chappell, Downriver, Radon Daughters - read like a dream, often a ripe nightmare of precognitions, the howl of ancestral voices as the shamanic scribe slums and bums his way around the psychogeography of England, the crusted Matter of Britain. As if Alfred Watkins, the old photographer who rode the ley-lines on the Hereford hills, were re-incarnated as Kerouac.

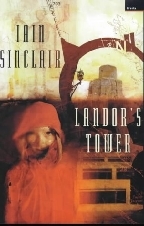

Landor's Tower is set in and around the Anglo-Welsh borders and the Welsh valleys where Sinclair grew up. The first-person protagonist Norton is returning to these zones after years in London, in an attempt to write a novel about Walter Savage Landor, the nineteenth century eccentric landowner who made a disastrous attempt to set up a rural community at Llanthony Priory. Indeed the whole area seems to have been a Bermuda Triangle in which successive utopian communities have foundered, including a dubious monastery established by the Victorian mystic Father Ignatius and the more recent abode of love established by the artist Eric Gill to service his various wives, mistresses, children and animals. "This border landscape was ripe with markers, marrying the mental worlds of disparate writers; the living dead questing for confirmation".

But the writer is soon distracted by his peripatetic researcher Kaporal, a "media bum" who sends him cryptic tapes about mystery suicides in the defence industry and the Jeremy Thorpe scandal of the the seventies. The poet Gavin Tunstall and the artist Joblard want him to check out a spirit photographer who takes ectoplasmic portraits of the dead with a Polariscope. He's further waylaid by a somnambulistic affair with a woman running a book shop in Hay-on-Wye, the Anglo-Welsh border "town of books".

As a former dealer (and specialist in beat/boho literature) Sinclair knows the territory all too well. Like Dean Corso (= Moriarty/Gregory?) in The Ninth Gate he understands the power of the bibliophiliac obsession. It's certainly disconcerting to meet fictional characters you've actually done the business with, like the bullet-headed enforcer Driff or that erudite Uranian rough-trader Becky, while the home-grown mythologies of Hay - the 1977 burning of Hay Castle, the town's annual Fire Festival - merge in a pyrotechnical set-piece. Sinclair's mythopoiea enfolds the Scroll of Hay and turns it inside out, skewing the picturesque shots of tourist brochures into dark tableaux of grotesquerie.

In a further extension of the fiction/faction process, characters complain to Norton/ Sinclair about their representation in earlier works. Several self-made mythic figures like the cannabis buccaneer Howard Marks and transsexual pioneer April Ashley appear as themselves, thickening the juices of the anti-plot with their louche cameos. Taking his cue from Ballard, Sinclair recognises that the creatures of our media landscape have turned the domains of their names into global properties, generic brands. The book operates by contagion. Stories bleed into each other.

Yet there's more to this than a post-modernist romp around the fractal identity of a fabulist, more to unpack than a roman with a rusty key. The work is sub-titled " The Imaginary Conversations" and Norton's interlocutors are, as always in Sinclair's earthscape, the dead. Hay is a dead interzone , a borderland of the damned, the "Tiajuana of the Welsh Marches." Norton's rented cottage is a poltergeist-infested hovel. Memories of the dead flicker at the edges of Norton's awareness, coded into the stonework of Llanthony and the fractured outcrops of the hillsides. The in-scribing of Norton's mediumship isn't merely passive reception, either. As in Burroughs and Gysin, the prophetic magic of the word creates dangerous occurrences, Soon Norton is writing himself into a thriller scenario, in which he's suspected of murder and confined to an institution. Chronology and causality blur as he rediscovers the archeology of his own psyche, the rubble at the base of the dark tower, the slate ground of his being .

Altogether it's an extraordinary performance. Sinclair feels a kinship with the visionary novelist John Cowper Powys, whose "buggerly great books" explored the romance of Glastonbury and the ancient mysteries of Wales. But there's also the ghost of old Bill Burroughs extending its skinny hand and wagging a warning finger. "A paranoid is a person who knows the facts." In Landor's Tower, the "facts" dance before the narrator's eyes like a toxic haze of insects. Like one of Burrough's agents, he constantly feels the heat closing in. If language is a virus then Norton is the killer app. Sinclair's protagonist surely steals his name from the "Norton " in the opening pages of Junky who introduces Burroughs/Lee to heroin. (Norton's real name is probably Morelli, of course) while so many of the UK counter-culture low-lifes who stumble though the book are the descendants of the hustlers and dealers who hung around the Angle Bar near Times Square - whose script, in fact, was written for them by Burroughs and the whole Beat canon. In so many ways Landor's Tower is a book of lost souls, a book of the damned rife with Fortean omens.

This reporter has perhaps foregrounded the darker pleasures of the text, its splenetic poetic, the gamey language, like a rich dinner at Sinclair's house that once left him sprawled in the bathroom, befuddled with brandy, cigars and home movies about wicker men. There's also a lightness, even a tenderness of touch about the women, especially the absurdly named Prudence, and a pleasing sense of the surreal in the various erotic encounters. Yeats once said that "the doctors have told us that the dreams of the night are but phantoms of sexual desire - but of what is sex a phantom?" This sense of primal vision informs the whole book, a recognition of the sheer strangeness of the ground-zero of our desire and the quiddity of our quest.

©Paul Green