Big Sound at The

Wetherby Arms

The Wetherby Arms is

an ugly maroon-tiled pub on a windy corner at the wrong end of the King's Road,

the World's End. No groovy nymphs in minis here, just lugubrious men in donkey

jackets hunched over their pints, who grumble as these young students with mod

pretensions push through the engraved glass doors of the saloon bar and pay

their 4/6 for the Vincent Crane Big Sound, an heroic attempt to clone the

Graham Bond Organisation.

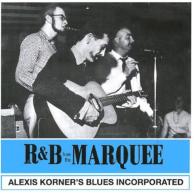

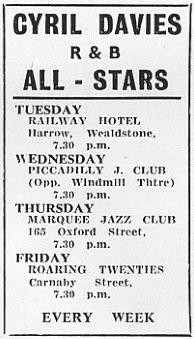

It's been advertised

in The Evening Standard small ads as "Rhythm and Blues without Guitars!!!" but

even this bold PR hasn't brought in the hipster crowd from the Flamingo or the

Marquee. The gloomy sepia room is almost empty. Behind the tiny stage members

of the Big Sound struggle with Crane's home-made PA and its fragile circuitry.

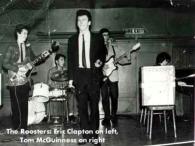

Still, here's my

Oxford room-mate Iain Stewart, with squeaky Franny from St. Martin's Art

School, and we're balancing beers and vodkas on a wobbly table, trying to plot

an image strategy for Vincent Crane, something that will get the Sound into the

colour supplements, along with Georgie Fame or the Who. Crane looks OK in the

band pic with his black shirt and shades and bop beret, and Pete the saxist is

changing his name from Pinching to Gifford (thank God Vincent dropped the

Cheeeeeesman!) and Mike the latest bass guitarist has to be better than that

jolly bloke last week with the string bass, and there's yet another drummer,

little Lew, who looks very serious.

We throw some phrases

around - "Crane's ruined Beardsleyesque good looks..." No, too pretentious,

even for the student press. But how about "music that goes beyond the itching

groin scene..." Hmmm. As Suzie with the flowing hair enters in her blue plastic

mac I realise that we are all deeply implicated in the itching-groin scene.

The speaker cabinets

hiss and crackle. A dumpy middle-aged man in a cardigan appears waving a

soldering iron. It's Ken Mundy,ex-Bond roadie and TV repairman, who has built

the Big Sound from old cinema speakers. "The turnip of the anti-trads?"

suggests Iain. Crane and Mundy then peer into the innards of the keyboard, a

strange Japanese single-manual affair like a poor man's Farfisa. We agree that

Crane needs a proper Hammond - there's a rumour that he's going to buy

Graham's, the one Ken sawed in half to spare the roadie's hernias.

Gifford, who's been

drinking since lunchtime, blows a perfunctory fart on his tenor and wanders off

stage. "Where's Roon?" he enquires, "I want someone to lend me ten bob. I am a

jazz musician... use the piano ...let's blow..." Roon - Mary Noonan, Vincent's

girl friend, hurries over and shepherds him back on the stand. "It's OK, Pete,

you'll be on any moment. I'll get you a half."

There's a sudden blurt

of notes from the amp and Crane, muttering, plays a few deafening chords.

Punters in the adjoining public bar cheer ironically. Little Lew thrashes

around his tom-toms. Gifford stops scowling and plays a graceful lick. As the

bass player adjusts his strings, Vincent counts in the Big Sound.

And the air throbs

with an organ riff - John Patton's Silver Meter - a spectral train boogie from

the depths of the urban night, a riff that drives right through our heads and

out the other side.

Who would have

thought that four guys with a toy keyboard, a tarnished sax and speakers in old

packing cases could create such a wonderful sinister noise? Crane launches into

a solo, all dazzling runs and filthy smears. Giff growls and howls at the moon.

This could be a soundtrack for beatnik orgies, although all would-be orgiasts

look too dazed to dance.

The Big Sound suddenly

stops in a squeal of feedback. Silence. A smattering of applause from the

illuminati. Crane stares around the room at the rest of his clientele and

gropes for the microphone. "Thank you," he murmurs sardonically, as if

addressing a class of remedial children. It's obviously time for something more

instantly recognisable as pop R&B.

So they try a Little

Walter cover - My Babe - a tune which VC invests with a strange aura, lewd and

melancholy at the same time. He's got Bond's London accent, no Chicago blues

intonations here, but there's a granulation in the voice which comes from

excessive Rizla consumption and although the singing thins out in the lower

registers, there's a rhythmic attack that carries it. The Big Sound are getting

on the case. Roon, Franny, and a girl with red dress are venturing on to the

floor. We're in with the In Crowd. Let's do the Hitch-Hike, the Cool Jerk. We,

cultists of the Big Sound, are looning it up on Guinness and last night's stale

pot.

The band works its way

through Water Melon Man, Bright Lights, Big City, Wade in the Water, Kansas

City, the whole 1965 R&B song book. In the gaps the rhythm section looks

anxiously towards Vincent while Gifford is grumbling about the failure of the

audience to buy him drinks. But Vin just shouts the keys and drives them on.

As we close in on the

stand, Giff thrusts his dented Selmer in our faces, Crane's ridiculous keyboard

sways wildly as he hammers it with that fierce left hand. After the leader's

hoarse desperate vocal, Crane and Giff fight each other for solo space, cutting

fours, overlapping runs, twisting phrases together like loops of barbed wire as

they compete to fill each bar with the urgency of our projected desires, the

suburban totemic blues of boys wearing Ray Charles albums on their sleeves to

bewitch the art-school girls, because this is the electrification of the soul

that's happening here, people, right here at the Worlds End with the blues.

©Paul A Green

««

CC

Audio

««

Media

Court

|