|

So Camilleri is upping

the ante on his protagonist (and the reader), who wants nothing to do with this

sort of evil. It's a playful rebuff to his critics while at the same time

underscoring that their choice of depravity and desire for sadism and deep

violence isn't his and that "Montalbano Says No". In actual fact, Camilleri's

crime fiction is brutal, but it's the joie de vivre style that offsets

the bad vibes by balancing comedy against tragedy, and his hero's affirmation

of life over 'man's inhumanity to man'. There's enough realism in the

Montalbano death scenes to make them credible, even if the TV pathologists out

there demand more.

'Montalbano Says No'

is judiciously placed near the end of this collection, and while you wouldn't

want this sort of game narrative to predominate, its inclusion at this point

adds an intellectual dimension that addresses, perhaps, a criticism that has

some validity. Camilleri is clearly a confident writer, relaxed enough to be

metaphysical if metaphysics are required, despite the appalling global demand

for voyeurism and photo-neurotic realism. He comes out of an Italian tradition

that includes Curzio Malaparte and Luigi Pirandello, writers who certainly had

plenty of contact with 'realism' but who chose to seek poetry in the absurdity

of life and the inherent contradiction of being and nothingness.

It's possible that the

'feel-good' critics base their objection on the TV series rather than an actual

reading of the Montalbano novels. Even if you've seen only one or two episodes,

you can't miss the burlesque production style, that much of the action has been

"sent up" -- to use theatre parlance -- and scenes edited to remove coarseness

and "excessive violence". While very nice to look at, the dramatization is

Prime Time, staged to avoid offending or upsetting sensitive men, women,

children and animals. But there's no reason why a filmed drama of the

Montalbano series couldn't be more real, accentuate documentary naturalism more

in line with, say, the Henning Mankell Swedish crime series 'Wallander' or the

Michael Connelly Los Angeles crime series 'Bosch'. Eliminate the buffoon

Catarella from the ensemble and maybe the Montalbano dramas aren't so funny.

It must be admitted

that some of the stories in this collection aren't 'short stories' but novellas

or discarded chapters or sub-plots from the Montalbano oeuvre. These are

episodic rather than axiomatic, and rely heavily on a previous knowledge by the

reader of the characters. It could be argued that the first long story --

'Montalbano's First Case' -- sets up the naive reader for all else that

follows, yet there's a sense of stasis to some of these tales as the supporting

cast doesn't evolve. Mimi is Mimi, Fazio is Fazio, and Catarella is just a

clown with one routine. The best stories -- or the ones that come closest to

the compressed narrative ideal of the short story are 'Fellow Traveller',

'Pessoa Maintains', and 'Judicial Review'.

The ending of

'Judicial Review' is probably too enigmatic for most addicts of crime fiction,

is too similar to the judge's dramatic suicide in a burning house earlier in

the story. But, like a surrealist painting, enigma can be its strength, forcing

you back into the imagery. Judge Attard, the man in black who walks the beach

in front of Montalbano's house, is like a metaphysical figure from a Giorgio de

Chirico painting, real enough, but unconstrained by time and space. With his

house jammed full of transcripts from a lifetime of trials and judgements, his

situation has the grim, Kafkaesque absurdity of a nightmare. Yes, you might

think of Pirandello or Borges, where symbolism explains everything and

nothing.

'Pessoa Maintains'

references a Spanish writer called Fernando Pessoa (1888--1935). While Pessoa

wrote under many aliases (or "heteronyms" as he called them), dabbled in the

occult (he corresponded with Aleister Crowley) and subscribed to Futurism, it's

his mysticism and logic that appeal to Camilleri/Montalbano, i.e., just because

the body is lying in the street doesn't mean the man fell down there. While

this might seem obvious, it does make a nice lead into the logic of this story

about a peasant poet (oral) called Antonio Firetto and his mafioso son.

Montalbano is called to investigate the death of a man in a rural house. The

man is sitting at the kitchen table, shot through the back of the head,

execution style... and turns out to be Firetto's son Giacomo, a mafia hitman

who has been on the run for a few years. It doesn't take the clairvoyant

Montalbano long to figure out who killed Giacomo; it's how he settles the

matter that provides the interest.

According to his

preface, Camilleri wrote 'Fellow Traveller' for a Crime Writer's "Noir in

festival" at Courmayeur (north-west Italy) in 1997 at the behest of the

organizers... and wouldn't you know it, a French writer who was also asked to

write a story, wrote one "essentially the same: both unfolded inside a railway

sleeper cabin with two beds, one occupied by a police inspector, the other by a

killer." Camilleri goes on to say: "Those present at the conference didn't want

to believe that it was a coincidence; they were convinced that the French

writer and I had worked it out together. But in fact we had never met or spoken

before then." Interesting... but does it make any difference to you or I now?

We think of Borges, of course, just allow this inside-outside metaphysical

possibility, admit that the universe is full of doppelgängers and destinal

conjunctions. Who, at least once in a lifetime, has not confronted the face of

Janus? Again, it's the simplicity of the plot, the sense of unity and its

inverted logic that makes the story interesting.

Others have strong,

pattern narratives. In 'The Cat and the Goldfinch' old women are shot and

robbed by a bandit on a motor cycle, his handler a cunning lawyer who has only

one real target in mind as part of his greedy masterplan. You might think of

Aesop's Fables here, although this cat-bird motif is introduced a bit late in

the action with no foreshadowing; Montalbano outwits the lawyer, of course, in

classic Camilleri fashion:

'Giuseppe Joppolo,

the handsome lawyer, lost his cool. "You don't have a shred of evidence you

fucking moron."

But then, of course,

since when did Montalbano need evidence?

In 'A Kidnapping' a

peasant finds a note inside a bùmmolo (a terracotta cistern for

keeping water cool), brings it to Montalbano. Simply, the note is a cry for

help from someone unknown. All the peasant can do is tell the detective where

and when he acquired the bùmmolo. While Poe's famous story 'Ms.

Found in a Bottle' might come to mind, Camilleri's is nowhere as convoluted and

picaresque; indeed, it's the very simplicity of its 'follow the thread' plot

that gives subtle power and an unexpected resolution.

'Seven Mondays' is

another acrostic, with a bizarre chain of animal killings that start with an

anonymous man concealed in a cardboard box on a wet chilly night. Perhaps

Camilleri was inspired by a children's book showing the evolution of the mammal

from the sea to the zoo. After an elephant gets whacked, the next target can

only be... well, once again Montalbano saves the day. This simple dialectic

demonstrates Camilleri's appeal for the general reader, where the child in the

adult can be indulged without ditching intellectual possibility, or the dark

side of life trivialized by 'feel-goodism'.

First story, last

story:

'Better the Darkness',

is an interesting choice to wrap up the collection. It has a very good opening.

A priest called Don Luigi Barbera approaches Montalbano, tells him about a

disturbing confession by a ninety-something old woman in an old folks home run

by nuns, but of course can't tell the Inspector what it is; instead, he drags

Montalbano to the old woman's bedside, and Montalbano has the eerie pleasure of

hearing one last line before she dies. The woman -- Maria Carmella Spagnolo --

whispers "It wasn't poison" that she gave her friend Cristina. Who, what, when?

This new but ancient mystery both attracts and repels Montalbano, perhaps

because of his antipathy to the priesthood, especially when Barbera says,

"Don't let me carry this burden alone, my son."

Yet... what's past

should stay in the past, and what the hell can Montalbano do about it anyway?

But he has a dream

about that infamous poisoner, Lucretia Borgia, and Barbera continues to bug

him, despite the fact that he balks when Montalbano says he is going to

investigate:

"Fifty years after

the fact?"

"You know

something, Father Barbera? Sometimes I ask myself what proof God had to accuse

Cain of murdering Abel. If I could, I swear I'd reopen the case." (p. 509)

Could it be that the

cleric is setting the naturally inquisitive Montalbano up? Like a woman

flashing her thighs to break a disciplined man?

'The old woman lay

sprawled out in an armchair, asleep, warmed by the sun bursting through the

windowpanes. Her head was thrown backwards and from her open mouth dripped a

shiny string of spittle, as her laboured, raspy breathing broke up moment by

moment, only to restart with increased effort. A fly passed undisturbed from

one eyelid to the other, which had become so thin that the inspector feared

they might cave in under the insect's weight. Then the fly slipped inside one

of her transparent nostrils. The skin on her face was yellow and so taut and

close to the bone that it looked like a layer of colour painted on a

skull.' (p. 546)

Is this a journey he

wants to take, a destination he wants to reach?

He has to go all the

way back to the early 1950s and to be sure, it's a fascinating tale... although

the narrative loses its identity in places -- too short to be a novel, too long

to be a short story. Despite Camilleri's easy, oral fluency, some of it is too

dense and expositional, especially those passages that paraphrase the trial and

conviction of Cristiana for the murder of her husband. Couple this with several

pages of filler where Montalbano runs the story past his associates and his

lover -- none of which advances the action -- you're left with verbal padding,

pure and simple. This isn't a criticism as much as it is an observation of

Camilleri's strength and preference as a writer, and the technical

difference(s) between the traditional and contemporaneous narrative methods

that are usually sweetly balanced in the Montalbano novels, just like a cleanly

draughted painting by Carlo Carrà or that master of bad taste

masquerading as good taste, Salvador Dali.

But sometimes not,

especially in terms of the short story or the 'American' objective style (or

'Protestant style'). Sometimes we get too much speculation, too much background

noise. Just cut to the chase, sir, we think. The short fiction narrative wants

to be existential, wants the action to reveal all. Despite the modernity of

Camilleri's novels, they are old-fashioned in that the hero makes everything

happen. This centricity increases as the novels progress and Montalbano ages...

although, perhaps, it's the same for all of us.

Camilleri over-writes

at times simply because he is fluent... and because the puzzle-narrative

encourages interior debate. Although a loner, Montalbano is sometimes an

internal motor-mouth. He rattles on, arguing with himself like a Pirandello

hysteric. There's a sense of schizophrenia in his character that increases as

the novels progress and he ages... although, again, perhaps it's the same for

all us.

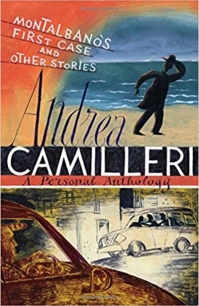

And the title story of

the collection?

'Montalbano's First

Case' will appeal to all who find the Montalbano series addictive, as it fills

in historical gaps without messing up the embedded fantasy. It won't replace

The Shape of Water or The Terracotta Dog as "the beginning of it all" -- the

shaping of Salvo Montalbano, genius cop, neurotic loner, social chump, and

apprentice mystic -- although it does confirm the obsessions and character

types. For example, the damsel in distress is a familiar Camilleri woman, the

erotic illiterate who only makes sense speaking body language: Rosanne Marullo,

zombie girl on a mission. Or there is the Honourable M.P. Torrisi, mafia

lawyer, a snake-tongue just like Guttadauro, the another loquacious mafia

lawyer seen in Excursion to Tindari.

As usual, Camilleri's

portrait of the Sicilian underclass is photo-electric:

Gerlando Monaco

(father of zombie girl):

"Mr. Inspector, try

to think. Isn't it enough to have a whore for a daughter without having a

bastard for a grandchild?"

And Montalbano's Sir

Lancelot complex in a nutshell:

"Now came the

question: was it proper for a police inspector to want to free the girl, give

her back her gun and tell her to shoot whoever she felt like shooting?"

Montalbano is a

liberal arts man with a credential in law, a '60's campus radical who exchanged

punches with the current police Commissioner, but now about to be promoted to

Chief Inspector. His reading recommendation this time around? 'The Blood of the

House of Atreus' by the French author Pierre Magnan. So the blurring of the

author and his alter-ego continues.

Livia, "Montalbva's"

on and off lover, isn't in the story; it's Mery, a old girlfriend from his

university days, who helps him move from his uneasy mountain posting in

Mascalippa, "a godforsaken backwater in the Erean Mountains", to beautiful

sleepy old Vigàta by the sea. Mery doesn't figure much in the action;

she's like a postage stamp, just a way of getting the hero from one place to

another and showing that there was life before Livia. Catarella? Not in the

story. Sergeant Fazio and Assistant Inspector Mimi Augello are there, take some

time to adjust to Montalbano's "off the books" method of investigation, the

psychic trickery and ad hoc decisions.

It's a mafioso story

and as to be expected, the new cop in town isn't one bit intimidated, and

indeed, quickly earns the respect of everyone concerned, including the

Cuffaros. Old readers will be satisfied, new ones intrigued, and critics left

to marvel at Camilleri's marvellous descriptive ability and psychological

understanding of Sicilian society.

But it's in the last

story that Camilleri has the last word:

'...why would he

want, by investigating, to turn a serial novel into a detective novel? Because

that was all he could aspire to: a good mystery -- and never, ever, one of

those 'dense, profound' novels that everyone buys and nobody reads even though

the reviewers all swear that they've never come across such a book in all their

days.'

(p. 512, Better the

Darkness)

Get it from Amazon

Canada

|

USA

|

UK

© LR June

2017

*Check out LR's

OUTLAW

ACADEMIC »»

or LR's novel

RADIO

BRAZIL »»

Other Montalbano

novels:

The Scent of

the Night [2005] |

The Wings of the

Sphinx [2006] |

the Paper

Moon [2008] |

August

Heat [2009] |

The

Dance of the Seagull [2009] |

The Age of

Doubt [2012] |

Blade of

Light [2012] | Death

in Sicily [2016]

|