Some deep dreams are so immersive they

almost leave a musky aftertaste - the flavour of durian or absinthe, perhaps

some faint odour of scorched metal or polystyrene. In those first moments of

waking your dawn is tainted by their ominous afterglow. Mike Harrison's

remarkable novel Light has that oneiric power, the stained light of a

sustained hallucination, a glowering illumination from the night-side.

Some deep dreams are so immersive they

almost leave a musky aftertaste - the flavour of durian or absinthe, perhaps

some faint odour of scorched metal or polystyrene. In those first moments of

waking your dawn is tainted by their ominous afterglow. Mike Harrison's

remarkable novel Light has that oneiric power, the stained light of a

sustained hallucination, a glowering illumination from the night-side.

Ostensibly it's an sf genre novel in galactic space-opera mode, involving star-ships, alien civilisations, hobo spacemen and multidimensional cat and dog fights. But Harrison has as much to do with the likes of old Ike Asimov as Philip Glass does to John Philip Sousa . He warps the genre through a dark worm hole into a highly personal hyperspace.

Yet this book hasn't created itself from nowhere like some random fluctuation of a quantum wave function. Harrison has been experimenting with the forms and metaphors of sf since the late sixties, when he contributed fiction and criticism to Michael Moorcock's seminal magazine New Worlds, a space where writers like J.G Ballard could challenge the complacency of the genre by tackling apocalyptic themes and exploring modernist narrative techniques.

Harrison's early book The Committed Men (1971) is in some ways a typical disaster-novel foray through a post-industrial Britscape of irradiated mutants but there's a very distinctive (and poetically bleak) sense of urban grotesque and horror. Characters move like damaged insects to the fractured rhythms of their memories. Short stories like Running Down (1975) embody the concept of entropy in the aberrations of an accident-prone sociopath against a wider backdrop of social - and even geological - decay, a disaster story in which the narrator himself colludes to provoke the catastrophe.

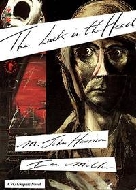

Harrison has always strived to expand the stylistic horizons of speculative fiction and explore exotic zones of consciousness. During the 1980s in the Viriconium series of novellas and short stories, he created a doomed alternative world of consumptive minor aesthetes "eating gooseberries steeped in gin" , endless Byzantine intrigue, obscure but barbarous rites. "Wherever you live in the city you can see the fireworks in the dark and hear the shouts on the wind..." The language is allusive, the tone elegiac but sinister, almost Huysmanesque. Ian Miller's drawings for his graphic-novel treatment of The Luck in the Head reflect this vision of menace and melancholy.

Yet Harrison's writing also keeps a tight grip on consensus reality and the material world. His mainstream novel Climbers (1989) won an award for its powerful evocation of the ordeals of rock-climbing, the neural charge of vertigo and danger. And throughout the body of his work there's a drive to confront the roots of the mythopoeic urge and redefine the function of speculative fiction. "We learn to run away from fantasy and into the world, write fantasies at the heart of which by some twist lies the very thing we fantasize - against..." (The Profession of Fiction, 1989)

Light deploys many standard-issue fantasy-kit devices as its raw material. In grubby dystopian modern London a mentally disturbed physicist develops the math that will eventually make interstellar travel possible. In the distant galaxies of the twenty-fifth century a young woman's body is bionically merged with a star ship. In a seedy twenty-fifth century spaceport a burned-out space pilot lets his life drift away in a virtual reality tank.

Harrison also uses the narratives of popular science as a starting point. Here quantum physics (and ancient alien technologies) provide the matrix of possibilities in which these three story-lines operate, allowing faster-than-light flight, surfing the rim of a black hole, skimming the event-horizon, infinite polymorphous perversions of space and time. The quantum foam is bubbling under, every little hubbly Hole is a Whole is a Hole. And there's always more of it... Reality duplicates itself fractally, quite madly, generating torsions, distortions, reflections, refractions of itself, yourself. "You can become anything you wannabe" as we tell ourselves on the telly.

It's the deep-end implications of this which Harrison explores, at an individual and at a cosmic level, transmuting his material in the process. He resists the tempting seduction of random narrative paths that fork off everywhere, whether they're the hyperfabulations of Robert Coover or the tasty worlds of Michael Moorcock where Jerry Cornelius copulates with a multiverse of mini-skirts. Harrison's three main narrative trajectories are all energised by characters with obsessive drives and haunted memories. To become what they wannabe they act; and their polyverse collapses into (pretty but often bad) shape around those choices.

Michael Kearney, physicist and serial killer, has been stalked since childhood by a presence he calls the Shrander, which seems to feed on his emotional isolation and sexual dysfunction. Four hundred years down the time-line Seria Mau Genlicher has irrevocably cut herself off from her abusive childhood (and her humanity) by choosing to merge her neurobiology with her K-ship "The White Cat," which she has stolen from her employers, Earth Military Contracts. She's bought some K-tech device from the gene-splicer Uncle Zip, and despite the pretty packaging, it doesn't seem to work. And after repeated sessions in the sensory immersion tanks of New Venusport, acting out C20 film noir heroics, Ed Chianese literally can't remember who he is/was any more.

The light that illumines these terminal survivors emanates from the Kefahuchi Tract, a stellar vortex of radiation and dark matter, surrounded by the wreckage of ancient civilisations that tried to penetrate its mysteries. The margins of the Tract form the Beach, where prospectors salvage exotic alien nano-technologies and artificial intelligence codes from the ruined worlds. Like Kearney playing on the beach as an infant (like Isaac Newton's famous self-description) they're half-comprehending children; and they're playing a dangerous game. The Tract eventually draws everything together, a node of psychic gravitation, like Rick's Bar in Casablanca....

That's not a totally frivolous comparison. Casablanca works as a film because of the tight integration of character development, plot structure and screen imagery; and Light works as a novel because of the poetic synergy of images and motifs that resonate between the different narrative strands. The substrate of the text is the substrate of quantum reality itself, so the traumas and ecstasies of Kearney, Seria Mau and Ed all finally wormhole into each other, but the clarity of the story always shines through.

Light illuminates everything in sharp detail, whether it's the biro-drawn tattoo on the hand of the satanic Valentine Sprake, who urges Kearney on his killing sprees, or the retro-fashion genetic engineering of the twenty-fourth century. The evocation of the Shrander, which slowly emerges throughout the book in an accumulation of surreal detail is one of the most disturbing creations I've read in years, on a par with Kneale or M.R James for its construction of sheer Otherness. "It swam with the little fishes in the shadow of the willow, just as it had sorted the stones on the beach when he was two. It informed every landscape. Its attentions had begun with dreams in which he walked on the flat green surface of canal water, or felt something horrible inhabiting a pile of Lego bricks. Dragons were expressed as the smoke from engines, while the mechanical parts of the engines themselves turned over with a kind of nauseous oily slowness, and Kearney awoke to find a rubber thing soaking in the bathroom sink. The Shrander was in all of that."

Light beams us into some dark spaces - the tatty rooms where Kearney and Sprake commit their atrocities, the chaotic warrens of the enslaved New Men on the corporate planets, the high vacuum where children's toys and body parts stream into the void after a K-ship skirmish. But there are also characters like Kearney's ex-wife Anna and Ed's companion Annie the Rickshaw Girl who, despite their own conflicts offer their partners some focal point beyond the solipsism of the technologically enhanced self. There are no easy redemptions or smart-weapon heroics. But there is at least an aperture to a new kind of self-knowledge, a new beginning.

"Mankind will become better and more evil" claimed Nietzsche. It is to Harrison's credit that he's been able to show us what this might involve as our techno-enriched future hurtles towards us and we stand transfixed in its glare.

©Paul A Green 2003