THE CITY AS NECROPOLIS

Citizens disappear constantly, along with their homes, artifacts, buildings and spaces. As your time-flow accelerates, old friends email the latest obituaries and the function of the writer becomes increasingly clear. You're there to count the dead; and re-count the missing landmarks. Scribe of mutability and mutation, you're only a memory-shaman, chronicler of the crumbling scrolls - destined yourself to become a mere neural trace in the world-brain, as the towers tumble around you.

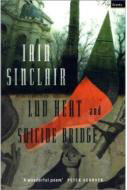

And this is the role that Sinclair has taken upon himself over the years, since mapping the psychogeography of the East End in Lud Heat circa 1975. Like a London cabby he's grafted "The Knowledge" of the city labyrinth the hard way, walking the streets, exploring networks of memory and urban myth, making the connections with the city's evanescent past. Others – Will Self, Peter Ackroyd – have tried to muscle in on the territory, and have done so with a certain panache. But Sinclair remains the Guvnor, closest to the heat, the dead heat. In this extraordinary anthology he's invited poets to dredge the rivers of memory or dug up memoir fragments from the lore of the Jewish diaspora, pub chat of retired gangsters and the recollections of footsore book-runners.

The common theme is "disappearance", either of persons or places or objects, a brief that encompasses Kim Philby's vanishing act, Kafka's hair-brush, forgotten war memorials, obsolete trades, all those shadowy spaces of dereliction or decay. Many of the contributions are factual, even autobiographical. Others go back to the London of De Quincey or Blake. There are several overt fictions, as a few factions, urban mythopeia intermeshed with reminiscence. The collection is a riposte to official notions of "heritage" and the neatly packaged experience of “tourist trails”. It is like an assemblage of relics from bombed sites, the playzones of so many post-war London kids. If you have any previous connection with such material, the effect of this bricolage is weirdly interactive. You drop yourself right into it.

Brother Paul:

London was the backdrop of my youth and like most environments, was only semi-visible when I was living in it. Now, exiled in rustic Hereford, my various fragments begin to mythologise themselves in brighter detail as I read. I recognize the faces of some of the old Poetry Buzzards from the sixties to the eighties, and I get ghostly flickers of some of the places where I/we flapped around and fell over each other, perhaps without recognizing each other at the time.