Directed/produced by Val Guest; b & w Dyaliscope with some

tinted scenes

Screenplay by Val Guest & Wolf Mankowitz;

starring Edward Judd, Leo McKern, Janet Munro

Photography by Harry

Waxman with Special Effects by Les Bowie

Music by Stanley Black,

"Beatnik Music" by Monty Norman

Pax Films/British Lion 1961

DVD by

Anchor Bay includes commentary by Guest and interview with

McKern

"THE INCREDIBLE BECOMES REAL!"

|| When Siegfried Kracauer wrote Film - The Redemption of Physical Reality in 1960 he seems to have meant "redemption" to be understood in an aesthetic context. "Film is uniquely equipped to record and reveal physical reality and hence gravitates towards it." Corollary: realism is the natural language of film. Yet you could also read "redemption" in a mystical sense, film as a Proustian dream-time, a time-capsule of liquid memory. Certainly watching The Day the Earth Caught Fire again after forty-four years takes me into a deep time-slip, a strange overlap of worlds.

In 2005, the film seems to exist on a ghostly reality level. It works now as a personal time-machine, shifting me back to a shadowy world of Remington typewriters, Morris Minors, dance music on the BBC Light Programme and cigarettes as signifiers of cool. London is on the cusp of the sixties, where protest and youth cultures are breaking through, but social and sexual mores are still semi-formalised and girls work in typing pools. We see a media landscape that is largely defined through the press and its heavy-duty Gutenberg technology, and a political landscape that is defined through the Cold War. The film depicts one particular retro-future in the diversity of universes, an apocalypse that hasn't (yet) happened.

But in the time-strata of 1961, where I'm sitting as an adolescent in the back row of the Wimbledon Odeon, the film is indeed incredible. I'm initially mesmerised by the pert lips and bright eyes of the incredible Janet Munro, by London's blazing skylines, by beatnik riots and the quickfire repartee of hard-drinking reporters.

Then the premise of the film - that nuclear tests alter the earth's orbit, disrupt the climate and send the planet spiralling towards the sun - makes a deeper impact. And the following October, as the Cuban Missile Crisis reaches its critical phase, the full after-shock of the sub-text hits me. Global destruction through nuclear war is becoming an existential reality.

Friday, 26 October 1962, afternoon : in the panelled library of Wimbledon College Father Healey is drawling through a lesson about Russian foreign policy in the eighteenth century. I read aloud robotically from a textbook but I can't connect with the wobbly text. We've all been scripted into the collective discourse of Kruschev and Kennedy's foreign policy. We still can't grasp that our chaps really might be tumbling into the Regional Seats of Government and scrambling the V-Bombers. The crews wear a single eye-patch, so when the fireball blinds them they still have one good eye to fly home, if it still exists. The Last Weekend starts here.

Nuclear holocaust anxieties in the movies were not new, of course. But these fears were usually externalised as monster mutation narratives, The giant irradiated ants prowling the Mojave Desert in Them (1954) typify a whole sub-genre of gamma-ray nightmare. Another influential narrative was the salvation myth. Benevolent aliens like Klaatu in The Day The Earth Stood Still (1951) intervened to warn humanity against its self-destructive folly. When Hollywood tackled the nuclear war theme overtly, as in Five (1951) or On The Beach (1959) the emphasis tended to be on post-disaster personal melodramas.

Since the early fifities Val Guest had been considering an ambitious film about the possible consequences of nuclear testing. Working in a genre like sf that demands high production values risked showing up the relative poverty of the UK film industry compared to Hollywood - as is demonstrated all too vividly by B-movie outfit Merton Park Studios in films like Konga (1960) where the ape-suits are even more awkward than the dialogue.

But Guest had already taken more of a realist approach to British science fiction in his Quatermass films for Hammer which feature sharp scripting and an economical quasi-documentary directorial style. Guest tended to use everyday locations or defamiliarise them like the oil refinery/alien food plant in Quatermass 2 (1957) rather than using exotic sets or props. Special effects were low-budget. To quote his matte painter, Les Bowie: "British special effects men had to do everything. We had to be powder men, water men, the lot..." In any event, after several years seeking backers, Guest had to part-finance the project himself, funded by the profits of his Soho coffee-bar movie Expresso Bongo (1959).

"THE IMPOSSIBLE BECOMES FACT!"

|| Exposition of data through dialogue is always potentially problematic in sci-fi. Guest and Mankowitz resolve the challenge by making their central character Peter Stenning (Edward Judd) a Daily Express reporter and sending him on a quest for data, aided by the paper's science correspondent Bill Maguire (Leo McKern) as a theorist and data interpreter. They're also very much rooted in an everyday mise-en-scene. The bustling newsroom with its exhorting wall poster slogans (Go for IMPACT! ) is a nexus of conflicting information and misinformation, conjecture and rumour as the hacks try to get an angle on freak weather conditions in the silly season. "I want facts!" barks their editor, Jefferson (Arthur Christiansen, former editor of the Daily Express). "Get on to the Air Ministry - Aldermaston - the Astronomer Royal!"

The "facts" gradually emerge through a fog of bureaucratic evasion and obstruction. Simultaneous Soviet and US megabomb tests at the North and South Poles have shifted the Earth's orbit, perhaps irreversibly. As a scientific premise it now looks very lacking in credibility - although in a period when the Russians were testing the fifty megaton Tsar Bomba it carried a certain plausibility for the non-scientist . However, it works effectively as a central metaphor and as the motivating enigma of the plot. And confronted with disaster as a fait accompli at the beginning of the film, we can suspend our disbelief more easily as we follow Stenning's quest in an extended flashback.

"ALCOHOLICS OF THE PRESS UNITE!"

The opening sequence is tinted in red (a feature missing in VHS reissues but restored in the Anchor Bay DVD). We open with the iconic image of the clockface of Big Ben, then pan across a dried out Thames and a deserted Trafalgar Square. The metallic voice of a police loudspeaker van intones a cryptic count-down. A long shot down Fleet Street gives us a glimpse of St Paul's and a first sighting of Stenning staggering through the heat haze into the Express office. The newsroom is deserted, his typewriter is clogged with dirt, so Stenning dictates his big story over the phone to a weary colleague, who protests, "We don't even know if there's going to be an edition tomorrow..." as we dissolve into flashback.

Three months earlier we're in mid-summer. In terms of news values reports of nuclear tests rank slightly below England's performance in the Test Match. Otherwise the newsroom copy boys are chasing stories about earthquake in Jakarta, floods in Devon, and atmospheric interference with radio and TV. Everyone's keeping busy except boozy Stenning, who clearly resents being tasked to write a lightweight piece about sun-spots, when he used to be the paper's hotshot columnist with serious ambitions as a writer. He'd rather be in Harry's Bar, a cosy all-day drinking club modelled on Fleet Street's El Vino's.

Chided by Bill Maguire, his irascible mentor and protector, Stenning admits his malaise, caused by his messy divorce and separation from his seven year old son, as well as a more generalised disgust at the futility of the race for atomic supremacy. "Anything you can split I can split better!" For Stenning the nuclear family itself has gone fissile.

Stenning's discontent is not explicitly political , in any specific ideological sense. His nihilistic rants in the earlier part of the film recall Jimmy Porter in John Osborne's Look Back in Anger or the Angry Young Man role that the media created for Colin Wilson. But there's the same restlessness about the restrictions of class. Stenning voices a distrust of traditional upper-crust Anglo-Saxon attitudes that parallels the increasingly awkward questions the narrative raises about the inertia of the British Establishment, as well as the mood of a Britain on the edge of social change. "You ought to see the way they're bringing him up, Bill. It'll be the right prep school next. And then the right boarding school. And by the time they finish with him, he'll be a right bowler-hatted, who's-for-tennis, toffee-nosed gent, but he won't be MY son...."

Reluctantly pursuing some factoids about sunspots, Stenning calls the Air Ministry and bawls out the sparky young girl on the switchboard, who doesn't treat him with the deference he seems to expect from women. He manages to blag his way into a Ministry meeting and upsets the pompous Sir John Kelly by pressing him on the connection between nuclear testing and climate change. Forcibly ejected, Stenning chats up an attractive office worker in the hope of getting a peek at a confidential report and gets a slap in the face when she recognises him from their earlier conversation.

This encounter with Jeanie signals the beginning of Stenning's slow transformation. It also exemplifies the transformation of gender politics in UK bureaucracy since 1961. Today a bright woman like Jeannie would probably be running the whole department rather than servicing a duplicating machine, which is where Stenning discovers her. "I'm not women!" she informs Stenning, when he makes one of his bar-room generalisations. But throughout the film Edward Judd and Janet Munro inject a crackling sexual energy in the roles, heightening the tensions beneath the banter. Judd is unrepentantly masculine, but also brings a slightly manic edge to Stenning's cynical one-liners - the theatricality of the alcoholic - while Munro transcends the cuteness she deployed in her earlier films for Disney, emphasising Jeannie's independent spirit and sexual confidence.

"I HAD TROUBLE WITH SUN-SPOTS"

When Stenning returns to the Express he finds that Maguire has covered for him by writing his sunspot feature , while a new story about the latest Russian test - "the biggest jolt since the ice age" - has just broken, forcing hectic last-minute resetting of the front page - "a slip edition" . This process is shown in lovingly documented detail. Today the sequence reads like an elegy for the old Fleet Street culture of "The Print" which gave life-time employment to thousands of Cockneys, until Murdoch introduced computerised newsrooms, smashed the print unions and moved operations to Docklands, eventually dragging the rest of Fleet Street with him.

Here ancient typesetters nod stoically as bluff foremen telephone the changes through amid the din of huge cumbersome linotype machines and rotary presses. These men are depicted showing a certain dogged resilience and pride in their craft, in contrast to Stenning's self-indulgence. Indeed, throughout the film, there's a similar emphasis- perhaps naive in a contemporary context - on the upbeat professionalism and integrity of his colleagues, whether they're digging out facts from evasive government sources or dealing with the increasing privations of the climate changes. "Whatever happens the paper goes on!" insists Jefferson.

So maverick Stenning, still in disgrace, goes on to cover a CND demonstration in Trafalgar Square. (Guest filmed an actual demo and intercut it with a staged scuffle between anti-bomb and pro-bomb supporters - clashing banners, fisticuffs, people thrown into fountains.) But Stenning discards the leaflets thrust into his hand. Then the sky darkens. The crowds stare up at an unscheduled solar eclipse. Stenning manages to photograph the flaring black disc of the sun - a superb piece of metonymy for the looming threat of extinction.

Trafalgar Square, 1965. I've joined Iain and Franny on the final stages of the CND march from Aldermaston as it surges up around the column, the stone lions and the fountains. We're pressed tight near the front, by the steps of the National Gallery where blues singer Ram John Holder is shouting through an erratic PA. The rainbow coalition has assembled from all over the UK, but some parts of the spectrum are clashing. Seinn Fein activists are brawling with Anarchists, and when a prominent Labour MP takes the platform, she's shouted down by the Spartacist League.

"Olive Gibbs is a Quisling! " Then poet Jeff Nuttall, author of Bomb Culture, takes the microphone. "I'm very disappointed with you all. Twenty-five thousand people have just marched past the Ministry of Defence. And I didn't see a single broken window..." A copper takes notes.

As the heat wave intensifies, Stenning takes his son Michael to another familiar London location, Battersea Park Funfair. The boy is fascinated by the faked terrors of the Ghost Train ride, with its pantomime masks and day-glo skeletons - an ironic counterpoint to the very real menace that's already materialising. Michael desperately wants "to live here" but the arrival of a disapproving nanny signals the end of Stenning's access period and the boy's tearful departure.

"LET'S HEAD TO THE NEAREST CAVE AND REPOPULATE THE WORLD!"

Stenning buys a paper and takes a wander through the park, an urban flaneur sizing up the bikini-clad talent sunbathing on the grass. Then he re-discovers Jeannie. His motivations seem mixed. The mutual attraction is strong but he's clearly interested in her admission that she has access to confidential information via the switchboard.

Their verbal fencing is interrupted by the ominous drone of fog-horns from the Thames. A huge wall of hot mist is rolling down the river. It quickly envelops the park. Les Bowie was apparently unhappy with his matte-work and fog machines but the imagery of flaring torches and dim headlights is convincingly reminiscent of the dense smog that so often smothered London life in the nineteen fifties. Soon the heat-mist is blanketing the city as the couple make their way through traffic chaos and increasing panic. Stenning comforts a lost child, indicating a gentler side to his character.

Jeannie warily allows Stenning into her apartment to phone the newsroom. A conference is in progress in which Maguire demonstrates the possible effects of nuclear testing on the weather. Jefferson is sufficiently convinced to run the story, with aerial photo-coverage from a helicopter, a panorama of London immersed in primaeval mist, totally immobilized.

The heat-mist also provides a tropical ambience for Stenning and Jeannie's affair. He returns to her flat, unable now to get home, but initially she insists he sleeps in the bathroom. The scene is unusually frank for the time. As Jeannie makes coffee, Stenning sprawls on her bed, toying speculatively - almost fetishistically - with her scattered underwear. He also ponders his proclivity to drink: "Maybe I will ...maybe I won't..." Jeannie prefers him sober and challenges him to make her fight for him. A call from the office brings him out of the bathroom, into her bedroom and eventually into bed, their desire heightened by danger.

Outside there's an accelerating montage of disaster, a cyclone that uproots trees, overturns Routemasters and hurls pedestrians across streets littered with debris. "It's like the old Blitz days," says a salvage worker next morning, looking at wreckage-strewn Fleet Street.

As I.Q Hunter points out in British Science Fiction Cinema the film progresses through a reprise of the city's collective memories and myths of World War Two - the Blitz, fire-storms, black-out, the miseries of rationing, evacuation of children, black marketeering and gangsterism. It raises the issue of whether post-war Britain could maintain the Dunkirk spirit in the face of a new threat. There's a hint, voiced by Maguire earlier, that "we've gone soft" and that under these new and even more extreme circumstances, social cohesion might unravel and give way to hysteria.

"THEY'VE SHIFTED THE TILT OF THE EARTH!"

Stenning's absences undermine his credibility in the Express office but he insists his "contact" in the Air Ministry will give them an exclusive. "I'm sick of being treated like I'm a cub reporter." Jeannie indeed contacts him. At a rendezvous in the fun fair, high on the slowly rotating Ferris wheel , she imparts overheard data but makes him swear to secrecy. She doesn't understand its significance but later Bill Maguire does. There's been a permanent eleven degree tilt in the planet's rotation. "We're going to print!" shouts Jefferson.

The sequence that follows has a disturbing contemporary relevance. Using a well-crafted blend of actuality and staged scenes, Guest creates a montage of drastic climate change - flood, drought, blizzard, monsoon and hurricane. Across Europe and the world the rioting starts. The Prime Minister, whose patrician tones recall Harold Macmillan or Sir Alec Douglas-Home addresses the nation with platitudes and little jokes about the weather.

As the UK temperature rises and water supplies dwindle, the fires start, in suburban parks - Richmond, Hampstead, Epping, Windsor - and urban warehouses. Once again Guest and his editor Bill Lenny worked with archive footage. There's a quick shot of a fire-engine from The Quatermass Experiment - but otherwise you can't see the joins. The broadcast instructions to "clear the roads for emergency services" recall the Civil Defence plans and disaster rehearsals that were already in place to deal (however desperately) with nuclear attack. Water rationing begins - and with it the first reports of water-poaching, anticipating the rival gangs of water-rustlers racing across the salt-flats in J.G. Ballard's novel The Drought (1965).

Stenning's relationship with Jeannie is also in crisis. She has been taken into custody for questioning. Unlike Sarah Tisdall, who leaked the British government's plans for the deployment of US cruise missiles at Greenham Common in 1982, she's not charged or imprisoned but she loses her job and her trust in her lover. As a gesture, Jefferson offers her work on the Express but she rejects Stenning.

Then the global crisis reaches a new plane. At a Moscow press conference, Russian scientists (formerly demonised as the enemy - now our collaborators) reveal that the explosions have not only shifted the tilt of the earth but have disrupted its orbit, setting us on a spiral course towards the Sun.

"WE ALL NEED WHATEVER WE CAN GET"

The camera tracks slowly along a line of grimy people queueing for water at a government ration station in Hyde park. Scuffles break out and tired policemen struggle to keep order. Stenning encounters his ex-wife who's seeking refuge in the country with their son and her new man. But old antagonisms have become irrelevant. "It all seems pretty ridiculous now," admits Stenning to his rival.

On the Embankment of the drained Thames, crowds stand silently around loudspeakers, like peasants in Maoist China, listening bemused to the tinny rhetoric of the politicians. Guest's documentary approach in these sequences anticipates Peter Watkins' cinema verite direction of The War Game (1964) or the plain style of Barry Hines' TV drama Threads (1984).

The scenes are doubly effective because of the director's restraint in using music which which throughout the film has been mostly diegetic - snatches of dance music embedding radio announcements - rather than operatic. There's similar understatement in the depiction of Stenning's reconcilation with Jeannie in the Express archive room, engineered by McGuire. Once again, the emotional baggage of the past has been dried out, burnt out. There's only an urgent recognition of mutual need.

"BEATNIK MUSIC !"

As the security situation deteriorates, Stenning heads for Jeannie's flat in Chelsea, despite the warnings of the cop at the roadblock played by a young Michael Caine: "It's pretty bad down there, sir!" Stenning: "It always was!" Chelsea, of course, was the Notting Hill, perhaps even the Hoxton of the late fifties, the focus of media panics about sex, reefers and dark glasses. In this hub of British bohemia minor aristocrats, mod fashion designers and art students mingled with the hairy boys of the British beatnik scene, creating the face of early British hip.

Guest and Mankowitz lock on to one of the tribal musics of that scene, "trad" or British revivalist jazz which - quaint as it might now seem - developed a wider youth cult following, even reaching the pop charts in the early sixties. In 1960 there had been riots between trad "ravers" and bop modernists at Beaulieu and and other jazz festivals - a tribalism choreographed by Julien Temple in Absolute Beginners (1986) - while trad bands frequently led the anti-nuclear marches. Here a frantic trumpet player is leading a rout of wild beat girls and bearded youths who overturn Stenning's car and shriek hysterically - as they hurl water at each other....

Is this an epidemic of infantilism, a playground water-fight at the end of the world? Or a display of nihilistic excess, like the rainbow lawn-sprinklers of the millionaire Lomax in Ballard's Drought ? It could be read as a metaphor for what Guest couldn't depict on the screen in 1961, the exchange of "our precious bodily fluids" (to quote from Dr Strangelove) in orgiastic doomsday sex. A screaming girl hurls herself at Stenning, gripping his waist with her thighs, and when he struggles through the melee into Jeannie's flat he finds a mob of youths and girls "trying to give the dirty little cow a bath", a tussle that seems to be spiralling towards sexual violence or even drowning as she cowers in the bathroom. Stenning manages to eject them after a fist fight in which a boy falls down the lift-shaft. Like Jeannie, he's in shock, dazed by the self-destructive frenzy of the crowd. "They'd rather it was all over..."

"COUNT DOWN"

|| The final scenes take us back to Harry's Bar and the Express newsroom. The major powers have agreed on a desperate strategy, the detonation of four huge bombs in Siberia, in the hope that the blast will correct the planet's orbit. Stenning, Jeannie and Maguire join the barman and his wife May as they listen to the countdown on the radio. Harry and May stop their bickering and admit their affection. There's a montage of locations - St Peter's Square, the Brandenburg Gate, the Champs Elysee - all still and empty. Down in the plant, sweating printers have been prepared two dummy front pages - WORLD SAVED/WORLD DOOMED. The moment of detonation passes, its outcome still uncertain. Then Stenning makes his way up a deserted red-tinted Fleet Street to file his story, a message of cautious hope. It is voiced over over the image of St Paul's, the iconic church that survived the biggest firestorm of the Blitz on 29 December 1940. As the image fades bells ring out - to signal warning or in celebration?

As I.Q Hunter says, "Stenning's sermon-like scrupulously apolitical voice-over adds a vaguely religious note which reinforces the modest utopianism to which the film aspires." Hunter makes the point that Stenning , through his love for Jeannie and his son, and through his commitment to the truth-telling news values of the Express, has found some personal redemption while the antagonisms of the Cold War have been neutralised and the world could be a better place after its ordeal. And in that sense, there's a basic humanistic reassurance. With a bit of the Dunkirk spirit, humanity might just make it...

In a contemporary context of global warming, asymmetric warfare, nuclear proliferation and dwindling resources, the film's underlying optimism seems touching. It is perhaps not as literally "incredible" as the film's scientific premise, but it contrasts with the darker vision of Kneale's Quatermass and the Pit (1967) which posits alien destructive impulses embedded deeply and inseparably within the human psyche: "We are the Martians now..."

Kneale's films, like Ballard's disaster work, could be read also as fables of alienation, atavism or even post-humanism. The post-nuclear imagination, embodied in Ballard's Terminal Beach is the precursor of the post-modern psychic ruptures examined in The Atrocity Exhibition. And the dominance of CGI hi-action spectacle in modern disaster flicks like Deep Impact (1998) or The Day After Tomorrow (2003) almost seems part of this dehumanisation process. A set of phenomena is the hero. If Bruce Willis or Tom Cruise or their ilk are incinerated, I do not care.

In this sense my personal nostalgia for The Day The Earth Caught Fire could be almost interpreted as a kind of regression, to a simpler age of Cold War certainties, the reassuring backdrop of London and its suburbs, the modest hedonism of the British Beats, girls with nice RP accents, a talkative epigrammatic verbal/print culture, where the script mattered and characters had interesting conversations.

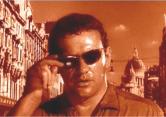

Summer, 198-, Wimbledon, South London. My wife and I are staying with my parents who now live just round the corner from the site of the defunct Merton Park Studios. Cathy returns from a shopping trip with my mother to report a strange encounter. "It's that Edward Judd," explains my mother, "One of our neighbours. He does a lot of those voice-overs for the television. I think he likes a drink or two..." Cathy describes an exuberant character with a deep tan and a gold chest medallion. He's full of bonhomie. "That film of mine's on tonight. The Day the Earth Caught Fire. My best part. You really must see it, my dears..."

©Paul A Green 2005